Julian Broad

Two world wars, one cold war, and a national history shorter than the rest of Europe's—how is a city to cope?Suzannah Lessard investigates the resurrection of Berlin's imperial and more recent past, in the architecture of the present

Julian Broad

Two world wars, one cold war, and a national history shorter than the rest of Europe's—how is a city to cope?Suzannah Lessard investigates the resurrection of Berlin's imperial and more recent past, in the architecture of the present

Americans now understand how architecture can occupy the center of a national psyche. We know that what we build at Ground Zero will determine how we collectively remember that catastrophe. Through an aesthetic alchemy, the right architecture will transform catastrophe into something else, a cultural depth, a kind of societal maturity. Such is the paradox of historical memory: no matter how terrible it is, acknowledging it is our only hope for the future.

Multiply the phenomenon of Ground Zero by 10,000 and you have Berlin. In Berlin—once the Nazi command center, and then divided between east and west—the physical city is the medium through which the identity of the new, unified Germany is being forged. There one feels the question pressing of how Germany, and indeed the West, is to go forward in this new century.

Architecture is the language in which such questions are approached: whether the Reichstag might again be used as a parliamentary seat, how the Potsdamer Platz, once divided by the Wall, should be rebuilt, what to do with the remnants of the Communist regime. But while I went to Berlin to see the buildings and places that have been at the heart of Germany's process of becoming, I wanted also to look at the architecture of earlier periods, at the layered history that is the context of these debates.

It is commonly understood that Germany must struggle with its Nazi past; less often appreciated is that the older, imperialistic past is also an issue in its reconstruction. There are medieval parts of Berlin—the remnants of a protective wall, the Nikolai Church—but it is really with the aristocratic confections built by the Hohenzollern dynasty that one enters a historical continuum that connects to the present and its concerns. For one thing, the Hohenzollerns were still in power when Germany plunged recklessly into World War I, putting the country on course for the defeat that created the conditions for Hitler's rise. But there are other ways, too, in which the architecture of the 18th century provides a background for what happened later.

Schloss Charlottenburg is the preeminent example of dynastic architecture inside the boundaries of Berlin. It was built in the late 17th century by Frederick I as a country retreat—on a site not yet part of the city— for his wife Sophia Charlotte. Its feminine, almost frivolous tone, its easy elegance, its highly cultivated atmosphere, could not be further from Nazi militarism, or modern realities of any kind. And yet the deep origins of the instability that led to Nazism can be found there.

Frederick's realm was Prussia, one of several small feudal states that made up what is now Germany. At the time of the construction of Schloss Charlottenburg, the Hohenzollerns had only recently managed to persuade the Holy Roman Emperor to recognize Prussia as a kingdom, though the promotion had to be qualified: Frederick was king in Prussia but not of Prussia because he did not control its eastern half. In this there is a taste of the ambitions of the Hohenzollerns, of how they felt themselves to be teetering on the edge of full-fledged power. A similar sense of being just short of superpower status would fuel Germany's ambitions for the first half of the 20th century.

There is no hint of this unease in the pale yellow palace with the red-tiled roof and the delicate green copper cupola that today sits in the wealthy west Berlin neighborhood of Charlottenburg. Two stories high, with stately windows front and center and two long wings that frame a central court, the schloss asserts the rightfulness of dynastic rule in a graceful yet imperious way. It is at once dainty and unquestionably royal—and indeed Frederick's purpose in building it was to express both those things, to convey a message of entitlement or decorous intimidation, depending on who you were.

There are large ceremonial rooms in the schloss, but much of it is intimate in scale. Off a long corridor, small beautiful rooms are laid out one after the other, in a French formation called an enfilade. On the other side of the corridor, windows look onto the extensive gardens that lie behind the schloss—disappearing into mist on the day I visited. Nevertheless, a feeling of claustrophobia began to set in as our guide led us from room to exquisite room. Each was a creation in which every inch worked to enrich: ceilings were painted with allegorical scenes, walls covered in patterned damask; a fireplace was lined with Delft tiles, a room entirely encrusted with displays of Chinese porcelain. Not a chink was left through which a reality other than that of Hohenzollern supremacy might shine. Was it my imagination or can you really feel the straining?

The Hohenzollerns felt inferior in every way to their cousins who ruled England and France, but what was most hurtful, perhaps, was the knowledge that the rest of Europe regarded Prussia as a realm on the outskirts of civilization. The obsessiveness of the emphasis on culture and refinement in the schloss conveys a fear of cultural inferiority.

Frederick II, who ruled during the latter half of the 18th century, had sterner ideas of royal grandeur than his grandfather and constructed a group of buildings, the Frederick Forum (Forum Fridericianum), on Unter den Linden that he hoped would turn the boulevard into Berlin's equivalent of the Champs-Élysées. He steadily expanded Hohenzollern territory to include long-coveted East Prussia (the Polish part) and Silesia. Of the Polish provinces he said that he would eat them "like an artichoke, leaf by leaf." Frederick II hoped to turn Berlin into a French city. He wrote histories of Germany in French, and French poetry that he submitted to his friend Voltairefor correction, though his verses did little to change Voltaire's opinion of Prussia as a place of horses and soldiers.

The Frederick Forum included the first freestanding opera house in Europe, since rebuilt many times; a small cathedral, St. Hedwig's, erected for Berlin's Catholics; a massive palace that is now part of Humboldt University; and a royal library that later came to serve as the university's. And it is in front of the library that the memories of imperial and Nazi pasts overlap: there, books culled from all over Germany were fed into a large bonfire in 1933 because they were deemed "un-German." A memorial marking the Nazi book-burning was installed in 1995 in the Bebelplatz, the semi-enclosed space formed by the library, the cathedral, and the opera house. The memorial took the form of a room lined with empty bookshelves, set beneath ground level, to be looked into through panes of glass beneath one's feet.

However, when I was there, the Platz had been torn up for reconstruction, excavated to a depth of about 12 feet. Exposed in the middle of this construction site, wrapped in murky plastic held in place by two-by-fours, was a cubic structure the size of a small room—the formerly subterranean memorial—a perfect image of the way Berlin conscientiously carries its terrible past forward, carefully wrapped for preservation, as it reconstructs itself for a new era.

When Berlin was divided, in 1949, the city's most important symbol of imperial power, the Royal Palace—a massive domed Baroque edifice that was the true seat of Hohenzollern power—fell into the eastern, or Communist, sector. It was located on the Museumsinsel (Museum Island), which sits in the Spree, the small river that winds through Berlin. The palace faced the Schlossplatz, adjacent to the Lustgarten, or Royal Garden, now covered in nothing but grass, the two together creating a large empty space around which elements of 18th-century Hohenzollern rule, 19th-century imperialism, and 20th-century Communism create one of the headiest mixtures of historical resonance in Berlin.The Communists, of course, had no use whatever for Hohenzollern memory, and so when, in the fifties, Walter Ulbricht, then secretary of the East German Communist Party, needed an important site for a government building, he summarily ordered the Royal Palace destroyed. In its place he put a rectangular box of a building, sheathed in gold-tinted glass, and called it the Palast der Republik, or Palace of the Republic.

The Royal Palace has been on the minds of Berliners, however. In fact, in 1993, the Palace of the Republic was wrapped in fabric imprinted with an image of the former Royal Palace. That bit of trompe l'oeil, which was sponsored by a West German corporation, is long gone, but a lengthy debate over what to do with the Palace of the Republic has been resolved in favor of tearing it down and rebuilding a replica of the Royal Palace, once enough money has been raised. It is interesting that the Germans are reaching back to the Hohenzollerns to anchor their identity, though it is hardly a unanimous decision. In the ferocious debate about the future of the Palace of the Republic, some argued that as the site of a totalitarian government, the building should be torn down; others, that because it was so ugly, to leave it standing would be the best possible way of memorializing the crimes of that regime. East Berliners said they were fond of the building (there used to be a recreation center with bowling there) and would like to see it remain. In the meantime, the palace was found to be loaded with asbestos and had to be closed for a costly cleanup that now, with the decision to tear it down, has proven to be unnecessary. Mixing issues of historical memory with democracy can be a messy business.

The Museumsinsel itself has been the focus of a massive restoration project that will not be completed until 2012. Of the other buildings around the Schlossplatz, the most important, architecturally speaking, is the Altes Museum, designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel in the early 19th century, in a forcefully dominant Neoclassical style, which had become the language of empire at that time. Schinkel served the monarchy faithfully, celebrating its supremacy during a period when monarchies were fast going out of fashion. Still, in moving from the 18th-century Frederick Forum to the 19th-century Altes Museum, one feels the sudden blast of modern reality—of the shift toward the far more dangerous mood of rivalry between industrially advanced nations.

The Altes Museum is a horizontally expansive building with 18 Ionic columns lining the front and 16 Prussian eagles, now blackened with soot, along the long, flat roofline. It was designed to house the great Greek and Egyptian collections that German archaeologists had brought home. All first-rate colonial powers had booty of this sort, and the Hohenzollerns wanted nothing more than to be on a footing with, for example, the British with their Elgin marbles. Flanking the entrance, at odds, in their kinetic energy, with the unyielding severity of the museum, are two large, somewhat hysterical bronze statues ofnudes on horseback, attacking and being attacked by lions. On the very top of the building stands a stiff sculpture of a horse rearing. Whereas other works of Schinkel's are smooth and elegant, there is an awkwardness about the Altes Museum—the perhaps overreaching extent of the façade, the possibly questionable proportion of the rearing horse. And in this very awkwardness there is a gritty sense of a culture straining and stumbling that seems specifically Prussian; here a style that is inherently serene and cerebral has a disturbing undertone of irrationality.

The Communist government had only contempt for antiquities, but it was underfunded, and tearing down a pile like the Altes Museum would have been expensive, which is why it still stands. We can also thank the East German government's lack of funding for the continued existence of the Berliner Dom, a massive cathedral in the neo-Renaissance style completed under Kaiser Wilhelm II, in 1905. Though any lover of architecture must wish that the Dom and not the Royal Palace had gone down under Communism, the Dom remains an interesting testament to the mood of the times, conceived as a Protestant retort to St. Peter's in Rome and as an affirmation that the kaiser was God's instrument on earth. Grand but hideous, soot-stained and neglected-looking, it is an astonishingly suitable memorial to an outmoded regime that reeled on into the 20th century, with tragic results. Next to it the Palace of the Republic stands ruined and abandoned, the image of the Dom darkened and distorted in its gold glass panels.

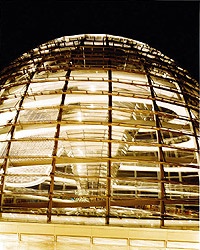

If one building could be said to have had a bombastic ideology of aggression and dominance at its core, it was the Reichstag. Erected to house the legislative body established by Otto von Bismarck, prime minister to the Hohenzollerns, it is now the parliamentary seat of the newly unified Germany. But this did not happen easily. Indeed, because of its turgid late-19th-century militaristic air, it posed what seemed an almost insurmountable problem of design. Lord Norman Foster's brilliant glass dome, however, has brought it into the 21st century through a kind of miraculous transformation.

A massive, heavily ornamented edifice that once had an ornate dome, the Reichstag presented a problem for contemporary Germans not so much because of its actual origins as because it seemed to epitomize the strain in the German temperament that led to Nazism. Ironically, some Nazi leaders disliked the Reichstag because of its association with democracy (the legislative body was elected by the people, though the kaiser had full veto power over its decisions). However, though Hitler liked the building, his party actually occupied it for only a very short time before a fire destroyed the interior and brought down the dome. By the time the Nazis took power, the Reichstag was a dismal wreck and the new government had to meet in the Kroll Opera house. And so the Reichstag sat, until the end of the century, like other buildings of its era, saved from destruction principally by the sheer cost of razing it.

After the Wall came down in 1989, the possible use of the Reichstag as the seat of Parliament was hotly debated. During this period the artist Christo wrapped the building in canvas. It was by many accounts a moving sight. Berliners would gather in front just to gaze at it.

Lord Norman Foster's solution for the Reichstag—once the decision had been made to use it—was to erect a new dome, but in glass, representing the transparency of government in contrast to the opacity and unresponsiveness conveyed by the old façade. The transformed building has been oft photographed but is one of those architectural marvels that must not so much be seen as experienced. Foster stripped lots of the ornamentation from the old façade, revealing proportions that are in fact quite handsome. But the dome is what does it. To reach the top, you climb gently spiraling ramps as you look out at spectacular, ever-changing views of the city. Connoisseurs of architecture tend to regard Foster's dome as too cautious and conservative. But the fact is that although it replicates a classical form, the dome in glass utterly transforms a building that was as difficult aesthetically and symbolically as a building could be. When, in the course of my climb to the top, I looked back to watch people entering from the elevator, I noticed a signature look coming over their faces—a bemused smile under a clear brow, quiet delight, a lifting. As a response to the Reichstag, that is really something.

Few physical traces remain of the brief period of constitutional democracy before Hitler came to power—the Weimar Republic—that gave birth to its own style of architecture, produced by the Bauhaus. The Bauhaus was primarily an educational institution and, with the Nazi ascendancy, did not last long (most of its practitioners fled to America). Consequently not much was actually built in that style in Berlin: parts of several underground stations and a low-cost housing block. Two impressive examples of Bauhaus design went up much later: the Neue Nationalgalerie, by Mies van der Rohe, and Philharmonic Hall, by Hans Scharoun, both built in the sixties. (So many cultural institutions ended up in East Berlin that West Berlin was obliged to reproduce them, making reunified Berlin a strangely duplicated city—two city halls, two national museums, two symphony halls, and so on.) Mies's museum and Scharoun's hall are near each other, in the area known as the Kulturforum, the museum a single story aboveground, steel-framed and with glass on all sides, and the hall a multi-sided shape that has the look of a Cubist ship on the high seas; inside, it is like a marvelous gourd of sound. These buildings project a mood of lightness, a happy world that does not look back, a posture that proved to be unsustainable for Germany, and indeed for the rest of the West.

Hitler had a vision of building Berlin as "Germania," but not much of this vision came to be. An exception was Göring's Air Ministry, on the busy corner of Wilhelmstrasse and Leipzigstrasse, in the former East Berlin; it now houses the Ministry of Finance. Designed by Ernst Sagebiel in the stripped-down, traditionalist style favored by the Nazis, today it memorializes a more recent history. A Socialist mural—sheaves of wheat and singing youths—still embellishes one side of the building; affixed to the other side, high up, are blowups of a demonstration against the East German government that took place in 1953. The photographs are easily visible as you drive down Wilhelmstrasse. From the sidewalk you can look through stately second-floor windows into one of the ceremonial halls in which Göring received visitors.

The imprint of Stalinist planning on the city is most visible on Alexanderplatz. When Berlin was divided, Alexanderplatz, previously insignificant, became the center of the Eastern side. I was shown around the area by Norbert König, a young art historian specializing in architecture who had grown up in East Berlin. He explained to me that where Western eyes see façades, Socialist eyes see buildings arranged in symbolic ways. Indeed everything about Alexanderplatz and its environs was freighted with meaning—the department store at which few in the past could afford to shop, the office building that housed the sole travel agency in East Germany (not far from the wall that was built to keep people in), the Haus der Elektroindustrie (House of Industry), the international hotel that saw few customers, the television tower. These were built in the sixties in the Internationalist Style previously rejected by the regime as corrupt but finally adopted out of budgetary necessity. The problem the Communists faced was how to make modern architecture symbolic. They solved this in various ways. The Teacher's Union, the first building to go up on Alexanderplatz in this period, was decorated with a Socialist mural.In the case of the House of Industry, passages from Berlin Alexanderplatz, a novel by Alfred Döblin that was critical of capitalism, were printed on the façade.

Leading into the Platz is a very wide avenue called Karl-Marx-Allee, designed for parades celebrating Socialism and lined with Modernist housing blocks that are spaced to dramatic effect. Toward the bottom of the avenue, the apartment buildings have a functionalist, traditional style similar to that of the Nazi era. They look more comfortable, more ample, but they were expensive to build, and when Khrushchev came to power in the late fifties he immediately ordered that a form of mass-produced housing be developed. That meant modern design. The system changed overnight.

Once the showpiece of East Berlin, the avenue is now in decline. For though the ensemble is grand in its way, the layout is not suitable to capitalistic enterprise. The Allee is too wide, and the buildings too far apart, for businesses to flourish. It's an extraordinary monument to a regime that compiled secret files on one-third of its citizens: another painful aspect of German history.

Formerly the commercial heart of the city, the Potsdamer Platz was divided by the Wall, and consequently became a wasteland. Rebuilding it, therefore, entailed creating a showplace for capitalism—the most extensive project to be completed in Berlin since reunification; one that has been much written about: photos of the forest of cranes went around the world in the nineties. The two principal "pioneers" at Potsdamer were DaimlerChrysler and Sony, both of which erected large complexes. Much of DaimlerChrysler's was designed by the celebrated contemporary architect Renzo Piano. The complex includes an office building with an airy atrium and a shopping arcade, and behind it there is a casino. In the Sony building, there is a striking space, glass-walled and sheltered by sail-like elements arranged in a circle. All this is fun, embracing the trend of architecture-as-entertainment, but not especially distinguished. The adjective that comes to mind is glitzy; the noun, mall. In other words, in the new Potsdamer Platz, physical emptiness has been replaced by a kind of cultural emptiness. We may feel condescending toward the Karl-Marx-Allee, but Potsdamer raises the question, Is this all we've got?

Well, it's not all, but to know that definitively you have to leave Potsdamer for the quieter district of Kreuzberg. There you can find the Jewish Museum, designed by Daniel Libeskind—author of the plan for Ground Zero, it just so happens. The Jewish Museum is symbolic without empty staginess; fulfilling in a spiritual sense while serving a practical purpose; difficult in its creativity—everything that the easy, consumer-friendly Potsdamer Platz is not: in short, it's a masterpiece.

With a zigzagging, lightning-like footprint, with zinc and titanium walls in which narrow windows are cut at unexpected angles and in unexpected shapes that, like the footprint itself, seem to be almost a kind of writing, with an interior where the floor sometimes slants and corridors end in bluntly expressive cul-de-sacs, and with a sunken garden accessible only from the interior, this building is symbolic in every respect. The garden is impressive from a distance as well as from within: willow oaks are encased in concrete planters so tall that only the tops of the trees peek out. The planters are set in rows well below ground level so that from outside you see just a portion of them, with the treetops bursting out, the ground tilting one way while the planters themselves tilt, in unison, in another. The garden does not so much express feelings as set in motion a mixture of hope and sorrow, loss and joy. And a part of that joy is the knowledge that in our Western culture, artistry can still be a match for history, that aesthetics can still provide a language for the collective experience of our time.

Berlin Architecture and Design, edited by Chris van Uffelen (Neues Publishing Co., $12.95). The perfect companion on a self-guided tour. • The third Berlin Biennial for contemporary art runs through April 18 and includes visual art, performance, and a film program (at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, the Martin-Gropius-Bau, and the Arsenal Kino; www.berlinbiennale.de). • Opening this month, Rosenstrasse, the latest film by Margarethe von Trotta, casts an unsentimental eye on the German women married to German Jews who, in 1943, held a seven-day vigil on Rosenstrasse, in Berlin's Jewish quarter, in order to secure their husbands' freedom. • Wolfgang Becker's Goodbye, Lenin! (awarded Best European Film at last year's Berlin Film Festival) comedically traces the efforts of a young manto spare his mother the shock of finding out that, while she was in a coma, the Berlin Wall came down.

—Kristine Ziwica

There are no direct flights from the United States to Berlin; you'll have to catch a connecting flight in London, Frankfurt, or another European hub. The city is large, but an extensive public transportation system makes traveling from neighborhood to neighborhood—even in the outer suburbs—easy.

WHERE TO STAY

Hotel Adlon Grand Hotel was filmed here in 1932, a little more than a decade beforethe original, turn-of-the-century building burned down. In 1997, it was lovingly rebuilt, with faithful reproductions of the coffered ceilings and stained-glass domes. DOUBLES FROM $306. 77 UNTER DEN LINDEN; 49-30/2261-1111; www.hotel-adlon.de

Dorint Sofitel am Gendarmenmarkt The building is a classic example of Plattenbau, the functionalist Modernism favored by the East German regime, but the interior is sleekly up-to-date. DOUBLES FROM $294. 50-52 CHARLOTTENSTRASSE; 49-30/203-750; www.dorint.de

Four Seasons Berlin All 204 rooms are spacious; most have balconies overlooking the Gendarmenmarkt and its 1821 Schinkel-designed Konzerthaus. DOUBLES FROM $380, 49 CHARLOTTENSTRASSE; 800/819-5053 OR 49-30/2033-6666; www.fourseasons.com

Grand Hyatt Berlin Designed by Rafael Moneo, this 325-room property is in the heart of the Potsdamer Platz. DOUBLES FROM $450. 2 MARLENE DIETRICH PLATZ; 800/233-1234 OR 49-30/2553-1234; www.berlin.grand.hyatt.com

Ku'Damm 101 The newest boutique hotel on the main drag of the former West Berlin. Clean lines and a minimal palette. DOUBLES FROM $190. 101 KURFÜRSTENDAMM; 49-30/520-0550; www.kudamm101.com

Ritz-Carlton Open since January, this Art Deco-style skyscraper on the Potsdamer Platz is Berlin's latest luxury hotel, outfitted with marble, bronze, and German imperial furnishings. DOUBLES FROM $460. 3 POTSDAMER PLATZ; 800/241-3333 OR 49-30/337-777; www.ritz-carlton.com

Schlosshotel Vier Jahreszeiten This 1912 villa, five miles outside the city center, in the leafy, residential Grünewald district, was remodeled in 1994 by Karl Lagerfeld at a cost of more than $20 million. The Lagerfeld Suite is furnished with the designer's own collection of Art Nouveau furniture. DOUBLES FROM $420. 10 BRAHMSSTRASSE; 49-30/895-840; www.schlosshotelberlin.com

WHERE TO EAT

Vau The first of the new restaurants in the former East Berlin to earn a Michelin star. Chef Kolja Kleeberg serves French- and Mediterranean-influenced food. DINNER FOR TWO $192. 54-55 JÄGERSTRASSE; 49-30/202-9730

Borchardt A famous French delicatessen and wineshop of the same name first opened here in 1853 but ceased operation when the Communists took over. Now a stylish French brasserie, the restaurant is popular with Berlin power brokers. The menu changes daily. DINNER FOR TWO $75. 47 FRANZÖSISCHE STRASSE; 49-30/2038-7110

Hugos Though the bird's-eye views of the Potsdamer Platz and the Tiergarten are impressive, it's German chef Thomas Kammeier's creations (turbot with cauliflower and dark veal stock; braised ox cheek with truffles) that promise to make this brand-new restaurant a lasting success. DINNER FOR TWO $185. 2 BUDAPESTERSTRASSE, 14TH FLOOR; 49-30/2602-1263

Gugelhof When former president Bill Clinton visited Berlin in 2000, this is where German chancellor Gerhard Schröder took him. Try the Alsatian choucroute. DINNER FOR TWO $70. 37 KNAACKSTRASSE; 49-30/442-9229

Hannibal The seats at this affordable Kreuzberg café (a short walk from the Jewish Museum) are salvaged from old S-Bahns. LUNCH FOR TWO $20. 69 WIENER STRASSE; 49-30/611-5160

Newton Bar A stylish cocktail and cigar bar named for Berlin-born photographer Helmut Newton, whose large-scale black-and-white photographs of nude women hang above red leather armchairs. 57 CHARLOTTENSTRASSE; 49-30/2061-2999

ARCHITECTURAL TOURS

Ticket-B Tailor-made tours of Berlin's contemporary and historic architectural highlights. HALF-DAY TOURS FROM $350 (FOR UP TO 25 PEOPLE). 1 FRANKFURTER TOR; 49-30/617-5452; www.ticket-b.de

—K.Z.