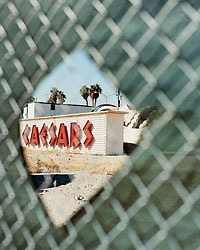

Bobby Fisher A vintage sign at the Neon Museum's Boneyard

When the world was haunted by atomic dreams, Las Vegas regularly saw mushroom clouds on the horizon. So it made them part of the show. Now an atomic museum and the desert itself spotlight an era's sobering kitsch.

Bobby Fisher A vintage sign at the Neon Museum's Boneyard

When the world was haunted by atomic dreams, Las Vegas regularly saw mushroom clouds on the horizon. So it made them part of the show. Now an atomic museum and the desert itself spotlight an era's sobering kitsch.

A little more than a year after the first bomb went off at the Nevada Test Site, the Last Frontier Hotel—an early theme casino on the Las Vegas Strip—crowned Candyce King Miss Atomic Blast. "Radiating loveliness instead of deadly atomic particles," as one newspaper caption reported, King was the first in a line of atomic pinup girls representing casino hotels over the next few years. The most famous photo had Copa showgirl Lee Merlin posing in little more than a cotton mushroom cloud, stiletto heels, and a big smile. But the girls were only the warm-up act for the main attraction: regularly scheduled nuclear explosions.

Between 1951 and 1962, the Department of Energy staged more than 100 aboveground tests in the Nevada desert 65 miles north of Las Vegas, gradually leaving the Pacific Ocean behind as too costly and unpredictable a proving ground. The Pacific's radioactivity loss was Nevada's tourism gain: fresh memories of Trinity, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki notwithstanding, then-governor Charles Hinton Russell noted that the desert was "blooming with atoms." Cars full of sightseers clogged the highways whenever an explosion was scheduled. Hotel marquees listed the "show" times. From bars facing north, patrons could watch the smoke roll up while they drank the house "atomic cocktail." Tourists would head to the higher floors of the big casinos to feel the building shake and the heat hit their faces. By the time of the last aboveground test, in 1962 (underground testing continued until a 1992 moratorium), the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, Gordon Dean, was moved to make the claim—admittedly dubious applied to the world's gambling capital—that the Test Site had brought more tourists to Vegas than anything else.

Nowadays, though Vegas nostalgically embraces fifties' memories of mobsters and ring-a-ding-ding—Sinatra at the Sands and Bugsy at the Flamingo—Nevadans as a whole have mixed feelings about the city's Cold War kitsch: a proposal to put a mushroom cloud on the state's license plate was passed in 2001 by the state assembly, then nixed in 2002 by the Department of Motor Vehicles as "insensitive to the times." Still, some 150 people a day go to the Smithsonian-affiliated Atomic Testing Museum, which opened in 2005. There they see photographs, films, and lectures about the Atomic Era (speakers have included Nikita Khrushchev's son and Dwight D. Eisenhower's granddaughter), as well as pop atomic artifacts like A-bomb–shaped salt-and-pepper shakers and far less playful objects, including the Geiger counters used to check workers at the Test Site.

It does not pay to stay up late indulging in Sin City vices the night before taking a tour of the Nevada Test Site. For one thing, it starts at 7:30 a.m. sharp. For another, it is a deeply sobering experience. There is no trace here of the camp and kitsch of the casinos, which is only appropriate; the NTS is, after all, an unintended monument to the dreadful costs of the Cold War. You might expect proximity to the apocalyptic to deter visitors, but the opposite is true—the Department of Energy tour buses are almost always full.

One stop on the Test Site itinerary is a two-story clapboard structure, bleached silver by years of desert sun. The inside is empty except for dust and bits of wall and ceiling that have fallen to the floor. It looks like an ordinary abandoned house, until the guide tells you that it was part of a small town built by the Atomic Energy Commission to see exactly what would happen to wood-frame houses, cars, and "people" (mannequins) when a nuclear device—in this case, the 29-kiloton Apple 2—was set off less than a mile away. JC Penney dressed the inanimate citizens of Doomtown, as it later became known, and after the test displayed them in its Las Vegas Fremont Street store window, accompanied by a sign reading, in part: these could have been you. Oddly, some of the figures looked only a bit askew, far less than "you" might expect to as a real survivor.

At Frenchman's Flats, where the first mushroom cloud rolled up over the desert in 1951, concrete and steel domes and bunkers were built to test the effects of an atomic blast on various kinds of fortifications. One structure, a bridge to nowhere made from immense steel beams, was bent into a smooth S-curve, like a sculpture by Richard Serra. And then there's Sedan Crater: a more or less perfectly smooth–sided cone descending 32 stories into the desert and measuring 1,280 feet across. It was made by a 104-kiloton bomb set off in 1962, only three months before the Cuban Missile Crisis. The crater is generally agreed to be among the most beautiful man-made "objects" in Nevada. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.

The dogged atomic aficionado can search out other, even stranger monuments to the effects of the Cold War in the desert surrounding Vegas. North of the Test Site is a town called Rachel—a tiny cluster of trailers that would likely have disappeared a long time ago if it weren't the closest settlement to Area 51, America's most secret military installation. In the 50's, the U.S. military tested the U2 spy plane here (Francis Gary Powers was piloting one when he was shot down over Soviet airspace on May 1, 1960). Still, nobody outside of Boeing, the Air Force, and the CIA thought much about the base until the 1980's. The antinuclear movement made it a protest site starting in 1986 (it still is, with much smaller numbers, today). And in 1989, when a Las Vegan named Bob Lazar appeared on TV to report that he had joined forces with extraterrestrials to work on a fleet of nine ships they were keeping in a hangar in a hillside, the idea that the government was hiding aliens and UFO's here began to enter the popular imagination. Area 51 began showing up in movies and video games, and TV shows explored the mythology of the base. Today, Rachel has learned to embrace its proximity to a clandestine military operation. The Little A'Le'Inn, the town's all-in-one hotel-restaurant-bar–souvenir stand and bookshop, attracts tourists as well as people who want to trade conspiracy theories and watch for flying saucers. The Little A'Le'Inn remains the only place along the ET Highway (formerly Highway 375) where you can get an Alien Burger and hear talk about how the CIA is in league with the Freemasons. If you want to stay the night, a few single-wide trailers are out back for guests.

Of course, Vegas itself still shows a few traces of the age of innocence. The Atomic Liquor Store bar on Fremont Street has been in business since the first tests were conducted. At Battista's Hole in the Wall, the stars who ate there when bombs still shook the earth appear in framed photos. The Golden Steer still serves the steaks and martinis Dino and the guys dropped in for when they weren't eating free at the casino. The big resorts from the early days are gone—a few of their iconic signs still shine at the outdoor Neon Museum on Fremont Street. As for Misses Atomic Blast and Bomb, both Candyce King and Lee Merlin have disappeared without a trace; but if you visit the Atomic Testing Museum, you'll find the iconic image of Merlin on the wall, in her A-bomb bathing suit. Shortly after the picture was taken, in 1957, she was laid off by the Copa. And by 1962, the tests had gone underground.

One of the most famous early test photographs, taken in 1951, shows the Golden Nugget Casino's sign lit up in the foreground, and the Pioneer Club's neon cowboy mascot, Vegas Vic, pointing his thumb toward the Strip. Off in the distance, toward the Pahrump Mountains, the roiling, radioactive cloud rises, dwarfing everything around it. If this seems crazy now, consider that the publisher of Las Vegas's Morning Sun was proclaiming at the time that after years devoted to the glorifying of "doubtful pleasures," the testing had, at last, "given the city a reason for existence." All these years later, hindsight—and perhaps some foresight, too—has introduced a little sobriety into Sin City.

Mark van de Walle is a contributing editor at Departures and is currently writing a novel.

Great Value: Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Rooms embody rock-and-roll glamour, just off the Strip. 4455 Paradise Rd.; 800/473-7625 or 702/693-7625; hardrock.com; doubles from $129.

Palms Hotel A young-Hollywood hot spot. 4321 Flamingo Rd.; 866/942-7770; palms.com; doubles from $199.

Atomic Liquor Store 917 Fremont St.; 702/384-7371.

Battista's Hole in the Wall 4041 Audrie St.; 702/732-1424; dinner for two $50.

Golden Steer 308 W. Sahara; 702/384-4470; dinner for two $110.

Little A'Le'Inn ET Hwy., Rachel; 775/729-2515; littlealeinn.com.

Atomic Testing Museum 5 E. Flamingo Rd.; 702/794-5161; ntshf.org; open seven days a week.

Neon Museum By appointment only. 702/387-6366; neonmuseum.org.

Nevada Test Site Once-a-month tours. 702/295-0944; nv.doe.gov/nts/tours.htm.