Some years ago, when a major Pacific Coast shipping company bought a two-page spread in Alaska Airlines’ in-flight magazine, the landscape chosen to represent Alaska’s grandeur was…Torres del Paine! An uninformed photo editor was the likely culprit. Fittingly enough for a Southern Hemisphere destination, the image was reversed. Nevertheless, the granite spires of Chile’s premier national park have truly become an international emblem of alpine majesty.

Lago Pehoe in Chile’s Torres del Paine National Park. Photo © Patrick Poendl/123rf.

But there’s more. Unlike many South American parks, Torres del Paine has an integrated network of hiking trails suitable for day trips and backpack treks, endangered species such as the wild guanaco in a UNESCO-recognized World Biosphere Reserve, and accommodations options from rustic campgrounds to cozy trail huts and five-star luxury hotels. It’s so popular that some visitors prefer the shoulder seasons of spring (Nov.-Dec.) or fall (Mar.-Apr.). The park receives more than 170,000 visitors annually, more than half of them foreigners. While Paine has become a major international destination, it’s still wild country.

Almost everybody visits the park to behold extraordinary natural features such as the Torres del Paine, the sheer granite towers that defy erosion even as the weaker sedimentary strata around them have weathered, and the jagged Cuernos del Paine, with their striking interface between igneous and metamorphic rocks. Most hike its trails uneventfully, but for all its popularity, this can still be treacherous terrain. Hikers have disappeared, the rivers run fast and cold, the weather is unpredictable, and there is one documented case of a tourist killed by a puma.

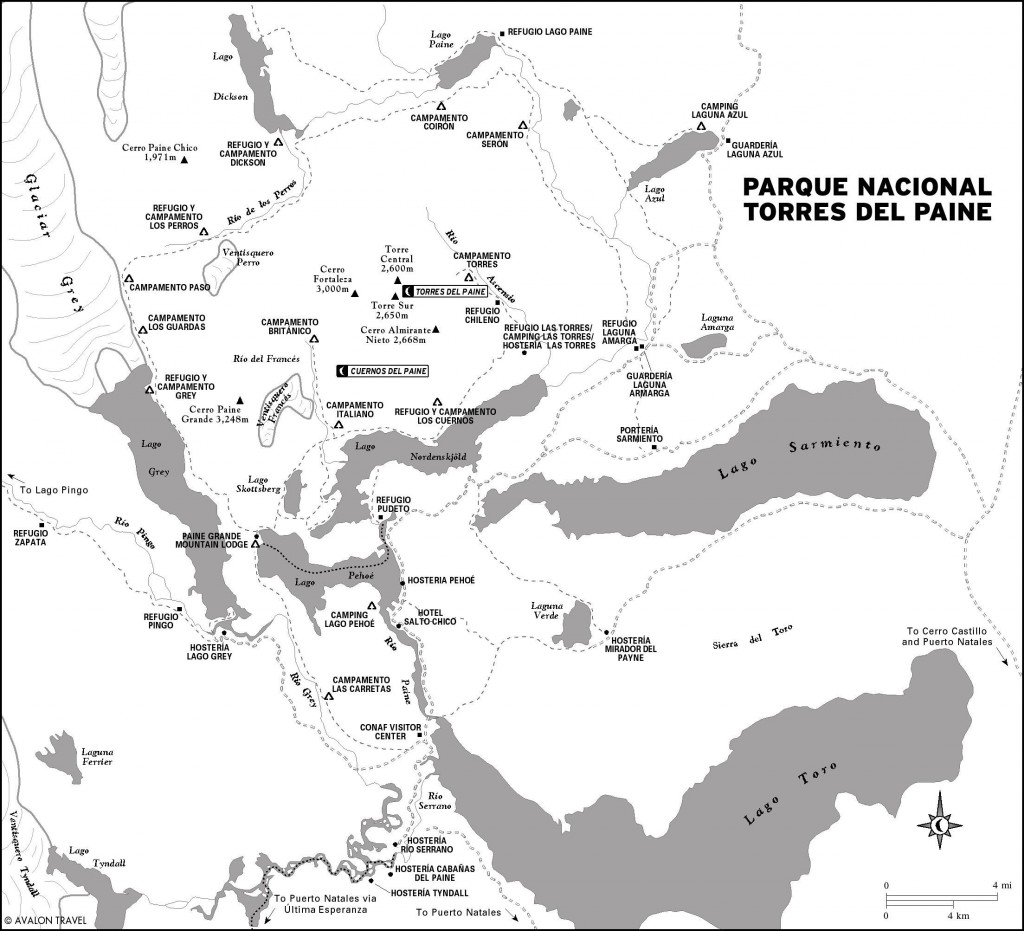

Parque Nacional Torres del Paine is 112 kilometers northwest of Puerto Natales via Ruta 9 through Cerro Castillo. Thirty-eight kilometers beyond Castillo, a westbound lateral traces the southern shore of Lago Sarmiento de Gamboa to the park’s isolated Laguna Verde sector. Three kilometers beyond the Laguna Verde junction, another westbound lateral leaves Ruta 9 to follow Lago Sarmiento’s north shore to Portería Sarmiento, the main gate; it continues southwest for 37 kilometers to the Administración, the park headquarters at the west end of Lago del Toro.

Twelve kilometers east of Portería Sarmiento, another lateral branches northwest and, three kilometers farther on, splits again. The former leads to Laguna Azul, in the little-visited northern sector. The latter enters the park at Laguna Amarga, the most common starting point for the popular Paine Circuit, and follows the south shore of Lago Nordenskjöld and Lago Pehoé en route to the visitors center. Most public transportation takes this route.

A bridge over the Río Serrano now permits access to park headquarters via Cueva del Milodón and Lago del Toro’s western shore, but this has not affected regular public transportation.

For foreigners, Torres del Paine is Chile’s most expensive national park—the entry fee is US$33 per person except May-September, when the fee falls by half. Rangers at Portería Lago Sarmiento, Guardería Laguna Amarga (where most inbound buses stop), Guardería Lago Verde, or Guardería Laguna Azul collect the fee, issue receipts, and provide a 1:100,000 park map that is useful for trekking.

Parque Nacional Torres del Paine

Parque Nacional Torres del Paine comprises 181,414 hectares of Patagonian steppe, lowland and alpine glacial lakes, glacier-fed torrents and waterfalls, forested uplands, and nearly vertical granite needles. Altitudes range from 50 meters above sea level along the lower Río Serrano to 3,050 meters atop Paine Grande, the central massif’s tallest peak.

Paine has a cool temperate climate with frequent high winds, especially in spring and summer. The average summer temperature is about 11°C, with highs reaching around 23°C, while the average winter minimum is around freezing. Averages are misleading, though, as the weather is changeable. The park lies in the rain shadow of the Campo de Hielo Sur, where westerly storms drop most of their load as snow, so it receives only about 600 millimeters of rainfall per year. Still, snow and hail can fall even in midsummer. Spring is the windiest season; in autumn, March and April, winds tend to moderate, but days are shorter.

It should go without saying that at higher elevations temperatures are cooler and snow likelier to fall. In some areas it’s possible to hut-hop between refugios (shelters), eliminating the need for a tent and sleeping bag but not for warm clothing and impermeable rain gear.

Less diverse than in areas farther north, Paine’s vegetation still varies with altitude and distance from the Andes. Bunch grasses of the genera Festuca and Stipa, known collectively as coirón, cover the arid southeastern steppes, often interspersed with thorny shrubs such as calafate (Berberis buxifolia), which produces edible fruit, and neneo. There are also groundhugging Calceolaria orchids, such as the zapatito and capachito.

Approaching the Andes, deciduous forests of southern beech (Nothofagus) species such as lenga blanket the hillsides, along with the related evergreen coigüe de Magallanes and the deciduous ñirre. At the highest elevations, little vegetation of any kind grows among alpine fell fields.

Paine’s most conspicuous mammal is the llama-relative guanaco, whose numbers—and tameness—have increased dramatically. Many of its young, known as chulengos, fall prey to the puma. A more common predator, or at least a more visible one, is the gray fox, which feeds off the introduced European hare and, beyond park boundaries, off sheep. The endangered huemul (Andean deer) is a rare sight.

The monarch of South American birds, of course, is the Andean condor, not a rare sight here. Filtering the lake shallows for plankton, the Chilean flamingo summers here after breeding in the northern altiplano. The caiquén (upland goose) grazes the moist grasslands around the lakes, while the blacknecked swan paddles peacefully on the surface. The flightless ñandú (rhea) scampers over the steppes.

Most people find the bus the cheapest and quickest way to and from the park. The route up Seno Última Esperanza and the Río Serrano by cutter and Zodiac is a viable, more interesting alternative. Tour companies from Puerto Natales usually enter the park at Laguna Amarga and loop back on the new road. Regular bus services continue to use the old highway.

Natales bus companies enter the park at Guardería Laguna Amarga, where many hikers begin the Paine Circuit, before continuing to the Administración at Río Serrano and then returning by the same route. Round-trips are slightly cheaper, but companies do not accept each others’ tickets.

Buses to and from Puerto Natales will also carry passengers along the main park road, but as their schedules are similar, there are extended daily periods with no public transportation. Hitching is common, but competition is heavy and most vehicles are full with families. There is a regular shuttle between Guardería Laguna Amarga and Estancia Cerro Paine (Hostería Las Torres, US$5.50 pp) that meets arriving and departing buses.

Transportation up and down the Río Serrano by a combination of catamaran and Zodiac, between the park and Puerto Natales, has become an interesting if more expensive alternative to the bus. Visitors who only want to see this sector of the river, without continuing to Puerto Natales, can do so as a Zodiac trip to Puerto Toro and back.

The traditional operator is Turismo 21 de Mayo (Eberhard 560, Puerto Natales, tel. 061/2411978, US$175 pp), which sails its eponymous cutter or the yacht Alberto de Agostini from a new pier at Puerto Bories to Puerto Toro and the Balmaceda Glacier, and then continues upstream by Zodiac.

Agunsa Patagonia (Blanco Encalada 244, Puerto Natales, tel. 061/415940, US$183-216 pp) has provided competition with newer catamarans that cover the route faster, in greater comfort, and with decent food on board.

October-April, reliable transportation is available from Pudeto to Refugio Pehoé (US$22 one-way, 30 minutes; US$35 round-trip) with the catamaran Hielos Patagónicos (Los Arrieros 1517, Puerto Natales, tel. 061/2411380). The first two weeks of October and in April, there is one departure daily, at 12:30pm, from Pudeto, returning at 1pm. From mid-October to mid-November and the last fortnight of March, there’s an additional service at 6pm, returning at 6:30pm. From mid-November to mid-March, there are departures at 9:30am, noon, and 6pm, returning at 10am, 12:30pm, and 6:30pm. Schedules may be postponed or canceled due to bad weather, and there are no services on Christmas and New Year’s Day.

Also in season, the catamaran Grey II goes daily from Hotel Lago Grey to Glaciar Grey (US$100 round-trip) at 8am, noon (one-way), and 3pm daily. On the return, it cruises the glacier’s face, so the reverse direction costs US$82 one-way. With a minimum of eight passengers, there’s a fourth round-trip at 6:30pm.

Excerpted from the Fourth Edition of Moon Patagonia.