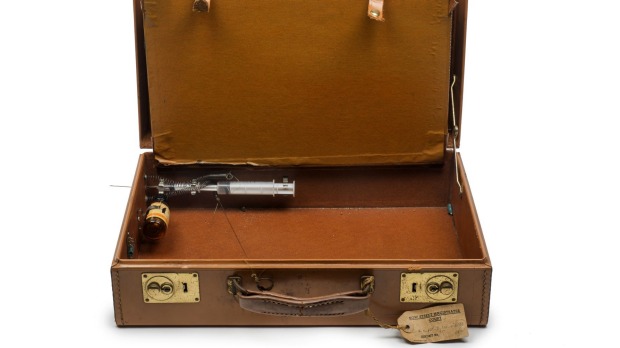

At first glance, it looks like your typical tanned-brown briefcase. Peer closer, however, and it becomes much more sinister. Protruding from a corner of the case is a spring-loaded syringe; beside it, a bottle of hydrogen cyanide. Described by a British Home Office pathologist as the "most deadly murder weapon" he had ever seen, the "poisoned" case could kill a person in less than eight seconds.

Ronnie and Reggie Kray – the twins who ruled London's underworld in the 1960s – are said to have ordered one of their associates to eliminate a gangland rival with the case. It was never used for its intended purpose, though, and ended up in the hands of the Metropolitan Police (the Met), the force charged with maintaining law and order in the British capital since 1829. Depicted by Tom Hardy in the recent movie Legend, the Krays – and their killer case – are just some of the menacing figures and objects featured in The Crime Museum Uncovered exhibition.

It's hidden in the basement of the Museum of London (MoL), a five-minute walk north of St Paul's Cathedral, in the shadow of the Brutalist Barbican complex. After charting the enduring appeal of Sherlock Holmes in one of last year's most acclaimed exhibitions, MoL's foray into true crime involves hundreds of pieces from the Met's "secret" Crime Museum (or the Black Museum, as officers call it).

Established in the 1870s at New Scotland Yard (the Met's headquarters), it's crammed with everything from ground-breaking evidence to criminals' personal property, and has, until now, only been open to police professionals and invited guests. So it's a treat – albeit an occasionally disturbing one – to peruse the selected exhibits.

The first two rooms span Victorian London, with a flurry of executioners' ropes and death masks of hanged criminals alongside notable exhibits such as the pistol used in a failed assassination attempt on Queen Victoria; tools belonging to Charles Peace – a notorious prosthetic-handed cat burglar – and courtroom illustrations of dozens of ne'er-do-wells (including a cheating Member of Parliament caught trying to arrange his wife's murder).

There's much speculation about Jack the Ripper, who committed a string of gruesome killings in the city's East End in the 1880s. Though several suspects are named here, a displayed memoir from a senior officer in charge of the never-solved investigation points the finger at Aaron Kosminski, a hairdresser living in Whitechapel. Moving into the exhibition's third – and largest – room, I'm drawn to the weapons seized from cons down the years (think: martial arts throwing stars, spiked clubs and a shotgun disguised as an umbrella). Other displays trace the advancements in forensic science and the Met's efforts to foil drug dealing, espionage, terrorism, inner-city riots and major frauds and robberies (vintage news footage reveals how police tracked down perpetrators of the 1963 Great Train Robbery, one of the biggest heists ever carried out in Britain).

Yet it's the 24-strong selection of criminal cases that will stay in the memory long after you've exited the exhibition. The cabinet focusing on the Krays is probably the most-viewed. Beside the "poison" briefcase, there are mugshots, press cuttings, a crossbow and the Mauser handgun that Reggie Kray tried to shoot Jack "The Hat" McVitie with. When the gun jammed, Reggie stabbed McVitie to death and was later imprisoned for life.

Other intriguing cases include those of Ruth Ellis – a nightclub hostess who shot dead her racing driver lover and was the last woman hanged in Britain – and Dr Hawley Harvey Crippen, an American who murdered his wife in London, fled across the Atlantic with his mistress and was subsequently arrested in Quebec by a Scotland Yard detective masquerading as a pilot. The most chilling exhibits on show? Possibly the rubber apron, gas mask and gloves used by John Haigh, a 1940s serial killer who murdered (at least) six people and dissolved their bodies in sulphuric acid. As I read about this morbidly fascinating case, I'm simultaneously horrified, yet wondering whether it has all the ingredients for a binge-worthy Netflix show: Making of an Acid Bath Murderer, perhaps?

museumoflondon.org.uk

visitbritain.com

Qantas, Emirates and Singapore Airlines are among the airlines that fly from Sydney and Melbourne to London. Running until April 10, the Crime Museum Uncovered exhibition costs £10 ($20.50). Entry to the Museum of London's permanent collections is free.