I'm travelling with Peter Schindler, a former Formula 2 driver who now runs the On the Road in China tour company. I'm glad of his expertise. The road is littered with rocks and ditches that would pass as canals in other countries. The rocks are so sharp they can shred your tyres if you're reckless. It's very slow going – 10km to 20km per hour. The scenery is stunning and changes from Alpine to primeval. It seems like every other bend has a waterfall fed by mountain meltwater. The road goes forever and continually teases with hairpin bends, steep drops off the side and views of the many miles ahead. You can often see the road etched into the side of the mountain ahead, stretching into the distance. We jerk like C3POs throughout the whole eight hours and finally cry with relief when we see a power station to mark the village of Kong Dang.

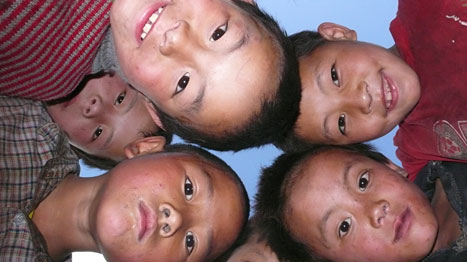

The Dulong river running beside the village is gorgeous. Its water has an aquamarine hue and is clear at the edges. Local Dulong people fish along the flat rocks that line the rushing river. The Dulong number roughly 7000 and are one of the smallest minority groups in China. They may lead secluded lives but that doesn't stopping them from leading similar lives to other people in China: they farm, fish, drink beer and their children go to school.

One tradition that has died out is the facial tattooing of the womenfolk. Xianjiudang village, 9km from Kong Dang, is home to two women whose faces bear these curious tattoos. The village is on the cusp of change. The village square houses a small school and a makeshift basketball court (the backboard is made of uneven wooden planks).

Just beside the basketball court, the village's only concrete building is home and office to the village leaders, or headsmen. The headsmen are dressed in army fatigues (a popular form of dress in remote villages as many of these headsmen have an army background) and they give the square the air of a derelict army base. A satellite dish sits outside and a Chinese flag flutters in the breeze.

My guide, Kong Yongqiang, takes me to see 66-year-old Gerzhi. She is unwell but agrees to see us. One quick pit stop to the local provision store for gifts (tea, milk powder) and we climb to a wooden hut on a hill. Gerzhi shuffles out from her house to meet me in a shed. She is petite, her frame slightly bent over a walking stick. I help her up some steps and we sit on wooden stools. Yongqiang helps me translate. It begins a little awkwardly.

I reach out and hold Gerzhi's hand and give her my widest smile. That breaks the ice, she laughs and tells me her story. When she was six, her parents burnt a piece of bark, stripped it and mixed it with ashes. They then tattooed her face with a needle, and rubbed the ash in. It hurt like hell for a week and no, she didn't want to do it. The origin of the practice is unclear, though she tells me it may have been used to make the womenfolk unappealing to raiding slavers. With the tattooing practice now banned by the Chinese government, Gerzhi’s daughter-in-law’s face is by contrast startlingly clear and smooth.

The meeting with Gerzhi touched me. I cried on the way down from the house. She had such joie de vivre. There was a spark in her eyes, her smile was coquettish and she was no way 66-years-old in spirit. I just wanted to hold her hand and hug her; to love her as my own family. I cried thinking that she was the last of a tradition that has existed since the Ming dynasty.