As another icy gust hurtled from the bowels of Kanchenjunga’s forbidding massif, Sarkhi cupped his hands around his mouth, tilted back his head and howled like a man possessed. “This,” he proclaimed, “is the sound of a Yeti.”

Now, high altitude can do strange things to your mind but, even in the Prek Valley’s rarefied atmosphere, Sarkhi’s howl sounded more werewolf than Bigfoot. I’d been introduced to the ‘Yeti Man’ (as my guide called him) outside the remote porters’ hut he tended in western Sikkim. Eight years ago he’d been carrying a load from Dzongri down the mountain when he’d stumbled across some sinister claw marks gouged into a tree.

“I was so frightened, I dropped my goods, turned and ran back home,” he explained, hunching his shoulders against the buffeting winds.

“So you didn’t actually see a Yeti?” I asked.

“No, but the claw marks were so deep they couldn’t have been made by anything else,” Sarkhi replied.

“But you have heard one?” I persisted.

“Yes, many people have, including my grandfather – but now the tourists’ arrival has frightened them all away,” he said, before returning to the sizzling yak-dung fire that filled his hut with malodorous smoke.

Sikkim, in many ways, is the eastern Himalaya’s Shangri-La. Fuelled by centuries of isolation from the outside world, fanciful tales of mystical beasts and mythical peaks have filtered out from this tiny Indian state. I’d read, for example, about Jan Frostis, a Norwegian uranium prospector, being mauled by a Yeti in 1948, and of monasteries founded by aero-dynamic lamas who’d flown over the Himalaya from nearby Tibet.

Nowadays, though, Sikkim is quite accessible. This once-independent kingdom, not much larger than New Delhi, woke up some 30 years ago to its strategic importance. Wedged between the Tibetan plateau and Indian West Bengal, it was the meat in the sandwich of a Himalayan power struggle between India and China.

With Tibet already occupied, Sikkim bowed to regional realpolitik and abandoned 300 years of royal rule overnight by ceding to India in 1975. Some areas are still militarily sensitive, but the Indian government has now opened much of Sikkim. And, while political instability has rocked neighbouring Nepal in recent years, the lure of Sikkim’s fresh hikes and the chance of viewing the southern face of Kanchenjunga (the world’s third-highest peak at 8,586m) is attracting a steady trickle of trekkers.

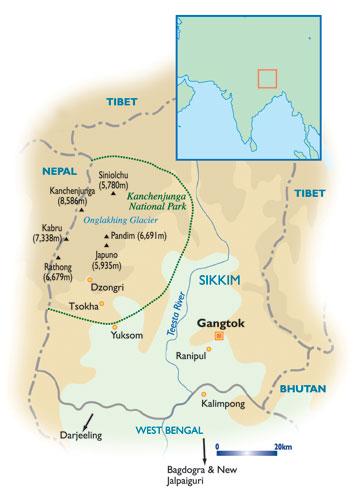

After joining Nawang Tsering, a Ladakhi mountain-guide, and five fellow trekkers (all Australians), we drove northwards from Bengal’s sultry plains. It was quickly clear that there’s neither a flat field nor a straight road in Sikkim. The roads zigzag back and forth like an ECG monitor as the glacier-fed Teesta, Rathong and Prek rivers carve vertiginous valleys during their thundering journeys southwards to eventually feed the Brahmaputra.

If at times our bus’ progress around the hairpin bends and frightening precipices left me gripping my seat, the scenery was compelling: sweeping terraces of lime-green rice paddies, lush forests, gravity-defying villages, lilac jacarandas and bottlebrush trees, huge stupas resembling hand-bells waiting to be rung, and avenues of prayer flags fluttering high on bamboo poles. To the Tibetans, Sikkim is Denzong: ‘The Hidden Valley of Rice’. To me, this wildly beautiful land was simply the greenest place I’d ever set eyes on.

Six hours west of the state capital, Gangtok, we arrived in Yuksom, the gateway to virtually all treks into the 1,874 sq km Kangchenjunga National Park. Stretching my legs (which pleased the local leeches) after the long journey, I took a stroll around the village. Some of the raffia-panelled homes are owned by Lepchas (‘the ravine people’), Sikkim’s original inhabitants. It is believed they were a tribe of wandering animist gypsies said to have migrated from the Indo-Burmese borders in the 14th century. They share Yuksom with the Nepalese, who now make up 75% of Sikkim’s population, and the Bhutias, a people of ancient Tibetan stock.

The Lepchas would have been well established here in 1642 when three venerable lamas founded Sikkim by crowning the first chogyal (king) in Yuksom. I found the coronation site amid terraces of cardamom in a compound filled by a forest of prayer flags. Four stone thrones remain under a huge, spreading cedar tree. Watching the land nearby being furrowed by water buffalo and ploughshare, it was hard to believe this sleepy backwater had once been the royal capital.

The following morning we started a seven-day trek into the mountains with an expedition contingent that would have justified an assault on Kanchenjunga’s summit. Four cooks, 12 porters, six dzos (part yak, part cow), their handlers, and Mr Jetta, the porter-sardar, seemed a tad excessive.

But, unlike some of the more popular Nepalese treks along which tea houses offer bed and board to trekkers, the Sikkim Himalaya has few such facilities, so our tents and food had to be carried. The dzos were placid beasts with wide handlebar horns, but would stop for nobody on the narrow, stony paths. Our lead dzo had a red-hennaed fringe and was adorned with alpine cowbells. “It’s a special puja,” explained Nawang. “The dzo drivers honour their oldest beast to pray for its long life.”

Our days on the trek began in style with a mug of steaming masala chai (milky tea spiced with ginger) delivered to our tents at dawn. For the first few days we ascended steeply through steamy subtropical forest: dangling lianas, epiphytes and wispy mosses cocooned virtually every tree. A glimpse of the occasional langur, a white-faced Himalayan monkey, was perhaps the closest encounter I had with anything remotely Yeti-like. In fact, far more likely to set the pulse racing were the antediluvian wooden suspension bridges spanning the Rathong’s glistening mica canyon, across which we’d edge whenever the river traversed our path.

By 3,000m, we’d reached one of Sikkim’s great spectacles, as tall stands of flowering rhododendrons and magnolias overwhelmed the forest. There are around 35 species of rhododendron in Sikkim; the dazzling shades and fragrant scents of apricot, scarlet-red and yellow blooms were intoxicating.

Amid the rhododendrons, above the confluence of the Prek and Rathong rivers, we entered Tsokha, the only village we’d encounter within Kanchenjunga National Park. Tsokha’s 15 families, I discovered, were descended from Tibetan refugees who’d fled the 1959 Chinese invasion.

South of the village, Nawang had taken us to visit Yang-Chan, another Tibetan exile. Her husband was away tending their yaks so she made ends meet brewing thomba (millet beer). She dressed in typically Tibetan style: a striped apron indicating she was married, and turquoise earrings, which shone against her weather-beaten skin. Her farmhouse was dark inside, like a cave, except for the flickering sparks lapping from the clay range. A boy churned butter-tea in a hollowed-out wooden container resembling a didgeridoo, while a portrait of the Dalai Lama, looking youthful behind his horn-rimmed glasses, was perhaps her only concession to decor. Soon we were presented with a bamboo cup of boiling, fermented red millet the colour of kidney beans.

“Sometimes the porters stop here for two or three of these,” Nawang explained, as we took turns slurping the pleasant, but sour, liquid through a straw. “They usually leave very drunk,” he added by way of a warning.

In Tsokha we visited a small gompa (monastery), fringed by brass prayer-wheels. Sikkim has over 200 Buddhist gompas and, like two of the country’s more illustrious monasteries – the beautiful Pemayangtse and Tashing, which we’d passed on the drive north – it had been built to be visible for miles. Inside, I watched its caretaker topping up the butter-lamps from a small vat of ghee, and I thought how tranquil it felt by comparison with Sikkim’s most famous monastery, Rumtek, which we’d visited a few days previously.

High above the river Ranipul, 22km from Gangtok, Rumtek’s sprawling temple complex is a little slice of Tibet. I’d paused to watch shaven-headed, boyish monks playing cricket and wrestling in their maroon robes, before entering the courtyard of an immense four-storey monastery. It’s home to one of the four schools of Tibetan Buddhism – the Kagyu, a 12th-century order whose lineage can be traced back to 200 years before the Dalai Lama’s first reincarnation.

Rumtek was built in the early 1960s by the Karmapa, the order’s spiritual leader, who’d fled the Kagyu’s centuries-old home in Tsurphu near Lhasa when the Chinese arrived. A golden dharma wheel tops the monastery’s roof, tended by two statues of deer, while multi-coloured gyaltsen (victory-banners), symbolising the defeat of negative forces, hang from the eaves. Inside the main prayer hall, fragrant with burning juniper, are riotously colourful wall paintings. I wandered across the marble floor, cool beneath my bare feet, watching the monks recite mantras near a gold-painted idol of the Sakyamuni Buddha seated in the lotus position.

The Kagyu sect is fabulously wealthy and I wondered where the monks stored their priceless symbol of power – a 14th-century jewelled ‘black hat’ said to be woven from the hair of 100,000 heavenly angels.

But something felt wrong. There was an uneasy atmosphere and a highly visible presence of armed Indian soldiers. For Rumtek, I learned, is at the centre of the most divisive dispute the Buddhist faith has known for years.

In the prayer hall I’d noticed a lavish throne, empty except for a framed photograph of a monk called Ugen Thrinley Dorje. This 18-year-old adolescent has been proclaimed the 17th Karmapa – the 16th having died in 1981. He was discovered amid the obscurity of nomadic life in the Tibetan wilds as the result of a predictive letter left by the previous Karmapa, but had to remain in Tibet as Chinese politicians fêted the boy – living proof to the outside world that the Tibetan faith could flourish under their rule.

Four years ago, however, he made international news fleeing Tibet to Northern India, claiming his religious freedom was being curtailed. But since arriving in India he has been ordered to stay away from Rumtek. The tension between China and India over his flight was bad enough, but I was flabbergasted when Nawang explained that open conflict had erupted during a bitter dispute between senior monks at Rumtek. One particular faction, now expelled from Rumtek, had offered a rival candidate as Karmapa, which has led to violence and court battles between the monks. By the portrait of Dorje, a monk – no older than the Karmapa himself – told me: “He’s coming soon; we expect him, but there are big problems with politics.”

By the time we’d reached the snowy Dzongri plateau (4,025m), unseasonably early monsoon clouds were threatening our views of Kanchenjunga’s massif. The mountain has always been elusive, with few expeditions ever being mounted through Sikkim itself.

“The Sikkimese won’t give permission to climbers as they consider the mountain sacred and believe it will lose its sanctity if scaled,” Nawang told me as we pondered the low, billowing clouds hugging the plateau.

Most summit expeditions enter via Eastern Nepal these days, and mountaineers still follow the tradition of Charles Evans (the British climber who almost beat Hillary and Tenzing to Everest’s summit in 1953) of stopping short of the final few metres to respect religious sensibilities.

Our campsite at Dzongri reminded me of an autumnal Dartmoor: an undulating expanse of squat, reddish-brown vegetation, smothered with junipers and dwarf rhododendrons rather than heather. The comparison ended whenever the milky clouds temporarily fragmented, allowing a brief glimpse into the leviathan world of mountains surrounding us.

Still, riding out the bad weather was no particular hardship: playing cards and drinking Sikkimese rum in the mess tent, and anticipating what Govinder, our Nepalese-born master of the portable stove, would conjure up for dinner. True to Sikkim’s cultural diversity, his cosmopolitan feasts of chicken ginger curry, thukpa (noodle soup), aloo gobi, momo, and the ubiquitous Nepalese trekking favourite, dal bhat, never disappointed.

Then, on the second morning at Dzongri, peering bleary-eyed from my tent before chai arrived, I witnessed the clouds cracking. Breathlessly gulping in the thin air, I made a hurried ascent of Dzongri La.

The rising clouds had already exposed Mount Rathong, which appeared like a sharpened fang to the west, and when I reached the tattered prayer flags marking the hill’s summit at 4,500m, azure-blue sky had broken through. The clouds peeled away westwards across the horizon like a theatre curtain promising an encore. First Kabru South and North (both 7,300m) appeared, before the Onglakhing Glacier, then Mounts Pandim, Japuno, and Siniolchu. The supporting cast was taking its bow, but where was the leading light?

Hesitantly, like a shy giant, Kanchenjunga’s southern massif finally revealed itself west of the Prek Valley; it seemed to float above the other peaks. John Hunt, leader of the 1953 Everest expedition, claimed that conquering Kanchenjunga would be ‘the greatest feat in mountaineering’, and I couldn’t help but agree, counting numerous complex peaks. Five of them top 8,000m, hence Kanchenjunga’s literal translation – ‘The Five Great Treasures in the Snow’.

I’d only ever seen one comparable view before in the Himalaya, in Nepal, standing at base camp in the Annapurna Sanctuary. Now, as a pink hue tinted the low cloud beneath Dzongri Hill, obscuring our campsite below, I could see powdery coronas of snow surrounding Kanchenjunga’s summits like ethereal spirits. Little wonder the Sikkimese revere it as the abode of the gods.

Joined by a few other trekkers camped close by, we picked out fluted ice-walls tinged turquoise and slabs of unstable-looking snow resembling chunks of marzipan. Only the distant, rumbling avalanches, the alpine-bells of grazing dzos and perhaps the odd yeti roar disturbed the calm of our stunned silence.

When to go: Sikkim has two short, distinctive trekking seasons bracketing the summer monsoon period. Between March and May it’s slightly hazier but you’re treated to the sight of rhododendron forests in full bloom. October to December is colder but offers crisp, clear views of the mountains.

Health & safety: Mosquitoes are not really present above 2,000m (beyond Yuksom), but complacency with regard to malaria should be avoided when travelling to the mountains through the West Bengal and Sikkim lowlands. Headaches or feelings of dizziness should be reported to your guide as AMS (acute mountain sickness) can strike anybody, regardless of age or physical condition, from 3,000m upwards. Consult your doctor before travelling.