A short step between freedom and fear

At first glance, the meeting table didn’t appear to be anything special. It was about 20 feet long, a yard wide and covered with a tablecloth that looked like it was lifted from a putting green. A black cord connecting microphones placed every few feet ran from one end of the table to the other, dividing it in half. The whole thing wouldn’t have been out of place in a conference room in almost any American corporation.

Two flags made all the difference; each about 18 inches high, at one end of the table. One bore the image of the seven continents against a baby blue background; the other, a red star encircled by white, set against a field of red and bordered by two blue stripes. These were the flags of the United Nations and North Korea. At that table in the Korean Demilitarized Zone’s “truce village” of Panmunjom, these swatches of international identity served as a reminder that the difference between freedom and fear is the width of that microphone cord, which marks the exact border between North and South Korea.

Because North Korea doesn’t permit independent tourism, stepping across to the northern side of the meeting table inside this UN-controlled building is as far as most Americans will ever get into North Korea, which along with Iraq and Iran, was declared to be part of the terrorism-sponsoring “axis of evil” by President Bush more than five years ago.

The average American would be smart to think twice, or even three times or more, before considering going to Baghdad or Tehran, but Seoul is safe. From there an extra $50.00 or so will get you on a DMZ tour that lets you stare straight into the eyes of a North Korean soldier.

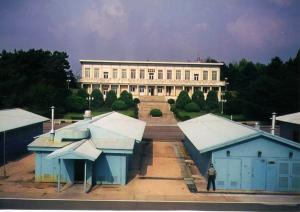

Freedom House Tower

Freedom House Tower

For sheer fascination, there is little that can be more intriguing than the DMZ. A few hours north is the North Korean capital, Pyongyang. More than one million northern troops have been waiting 50-plus years since the end of the Korean War for the order to head south. Even closer to the DMZ is South Korea’s capital, Seoul. There, 650,000 Republic of Korea (ROK) troops have also been in readiness for the same number of years to repel a northern invasion. Thrown into the mix are about 37,000 U.S. soldiers – who at times have been said to be the only roadblock to North Korea attacking south – and whose presence is always a matter of political debate in Seoul. At 151 miles long and 2.5 miles wide, the DMZ is the most heavily fortified border in the world.

A relic for the modern era

Everything about the DMZ smacks of a previous era. Yet the region remains immensely pertinent to modern world politics. It’s called the “Demilitarized Zone", but armed soldiers are everywhere – a throwback to the Cold War when the situation could have turned hot at any moment. Today the DMZ is a bulwark against a possible enemy in the war on terror. Almost all the places that epitomized the communist policies of Lenin, Stalin and Breznhev have embraced capitalism and its emblems, such as McDonald’s and Starbucks. But behind the DMZ is the last true communist holdout, and the most secretive nation in the world.

Getting to the DMZ is fairly easy. There are plenty of companies offering tours; all begin and end in Seoul. The tour I took was organized by the Korea Travel Bureau (KTB), a national tourism agency that is said to run one of the most comprehensive ones in the area. Prior to leaving, I was given a list of verboten clothing that would have impressed even the strictest Catholic school dress-code architects. No jeans, no T-shirts, no sandals, no clothing with any large, discernable logos of any kind. The regulations weren’t so much for formalities, rather for security concerns. The U.S. and ROK soldiers don’t want a group of tourists looking like they just walked out of some shopping mall. Potentially, this offends the North Koreans, who are watching and photographing the southern side.

I went to Seoul’s Hotel Lotte at nine on the morning of my tour where I met my group’s leader, a man who called himself Mr. Kim. He led fifteen of us into a room that housed several detailed topographical maps of the Korean peninsula. Highlighted areas included the Punchbowl, Heartbreak Ridge and the Chosen Reservoir – places where some of the bloodiest fighting in the Korean War occurred. Seoul itself fell four times during the war. It was virtually flattened by the time the conflict-ending truce was signed on July 27, 1953.

Times change. Seoul is bustling with business now. However, once I was out of the capital, I felt like I was a moving target. The bus wound its way through lush greenery that was both spectacular and foreboding. I knew something serious lay ahead, but I wasn’t sure what awaited me. It was hard not to feel somewhat paranoid; I almost expected the serenity to the broken hordes of North Korean troops roaring out of the brush.

Instead, American and South Korean soldiers periodically appeared on the sides of the road. They waved to the tour bus, but not without first giving it a serious looking once over. At the Joint Security Area (JSA), which is the official name of the region encircling Panmunjom, a U.S. Army specialist came into our bus. He greeted us with a slingshot salute and the motto of the United Nations Command Advanced Camp, stationed in the JSA: “In front of them all"!

The statement is more than a set of words. The troops in the JSA are the first line of defense in the event of any North Korean invasion. The JSA is an almost bucolic island in the verdant no-man’s land between North and South Korea. The compound is comprised of several nondescript meeting rooms. Outside is a man made pond ringed with fir trees and shrubs. It could pass for a small park in any American city, as long as you took away the camouflaged military vehicles and armed soldiers. Both U.N. and North Korean soldiers patrol the zone, yet they don’t have carte blanche to wander far across the border. If they did, they would be shot.

Shortly after arriving, we were led into a meeting room where we signed papers that absolved the U.S., South Korea and the U.N. of all responsibility for any incident that could result in us being shot by the North Koreans. Each of us was then given an identification badge adorned with the U.N. logo that had to be worn at all times throughout the tour. Under the escort of two U.S. Army soldiers, we were taken up into Freedom House, an observation post that gave me my first look into North Korea. About 50 years away stood North Korean troops dressed in the drab, chestnut brown uniforms that communist armies favored through the length of the Cold War. The North Koreans snapped pictures incessantly. Our army guide let us know in no uncertain terms that we weren’t to make any gestures at all toward the North Koreans. If you point your finger at them, they may point their AK-47 assault rifles back at you.

Looking into North Korea from Freedom House

Looking into North Korea from Freedom House

From Freedom House, we were led into a squatty, pale-blue conference room guarded on the outside by South Korean soldiers, one on each end of the building’s wall. The men appeared frozen, standing in the “ROK-Ready” position with half their bodies shielded by the building and the other half open to view their North Korean counterparts.

Stepping across the line

Inside was the table where U.N. and North Korean military brass meet to discuss whatever issue might be threatening the Korean peninsula’s stability on any given day. Our guide said that inside the conference room was the only place along the DMZ where tourists could step across the border and into North Korea. More than a few people let out brief, nervous laughs. The soldier said we could step over to the North Korean side “in relative safety".

It was at this point that the enormity of the situation truly hit me. Once I crossed that line and was officially inside North Korea, I felt I was doing my part to defy whatever is left of communism, one American footstep at a time. As I wound my way around the table’s long side, South Korea seemed miles away, not the merely two feet I had just walked.

Then, one of the women in our group let out a gasp. Four North Korean soldiers, two each on opposite sides of the building, began marching to the border, as though they were taking up positions for guard duty. Sure enough, they came over to the windows, watched us like dogs waiting for table scraps after a Thanksgiving meal. This was routine surveillance. Along with our American guide, we were joined in the room by two South Korean soldiers who stood opposite each other on the long ends of the table. The South Koreans looked straight ahead while the North Koreans stared through the windows and over their southern counterparts’ shoulders.

Koreans from both sides on guard

during a tour

Koreans from both sides on guard

during a tour

We were allowed to take pictures of the North Koreans. I fired off a few shots as though I was taking photos of lions at a zoo. Like the North Koreans, I was both a visitor and an animal on display. They looked at me with what felt like the cold eye of communism. I’m sure that to them I was the reason Korea has been divided for more than 60 years.

After 10 minutes in the conference room, our guide herded us up to leave. As we crossed the road between the conference room and Freedom House, I looked back at the border and saw that the North Koreans were about to lead a tour in through their side of the building I had been in. Just then, a couple of American and South Korean soldiers headed for the building to keep tabs on the North Korean group. The show at the zoo was beginning again.

The Korea Travel Bureau gives a seven-hour trip to the DMZ and Panmunjom. Lunch is included and reservations must be made at least one day in advance. can be found at Tour2Korea.

You can read Rex Crum's biography here.