How the tango took over Finland's over 50s

It was in the early 80s when two Finns, fuelled by beer and steam, hatched an idea for a tango festival while sitting in a sauna. The Seinäjoki Tango Festival now draws over 100,000 people each July to an otherwise unremarkable town near Finland’s west coast, and is a slice of Scandinavian midsummer eccentricity which throws as much light on the Finnish soul as it provides exercise for Finnish soles.

Perhaps it’s not so surprising that a country marked by empty distances and wintry solitude should be seduced by music based on longing and desire, and a dance involving close human contact. “The Finns are very melancholy,” admitted festival spokesman Ilkka Heiskari. “We drink too much but do not speak much. Tango is our language.” He paused. “And it’s the quickest way to get a lady.”

It was a view echoed by Heikki Hietamies, a renowned tango master of ceremonies. “The tango suits the Finnish mentality, especially the Finnish man,” he said. “The songs say things that he cannot say to his partner.”

The atmosphere on Seinäjoki’s streets, however, was more jollity than steaming passion. The main excitement centred on who would be crowned Tango King and Queen in the song competition which accompanied the dancing.

This is Finland’s answer to Pop Idol: a clutch of bright young wannabes whittled down from 1,000 early contenders, belting out crowd-pleasing sentimentality in front of TV cameras and packed auditoria. A fifth of Finland’s five million people watch the televised finals and, like Pop Idol, there’s even official betting on who’ll win, though the only thing which seemed a certainty, looking at the posters around Seinäjoki, was that they would all have great skin and razor sharp cheekbones.

A previous Tango King, Jari Sillanpää, was the hot ticket for my visit. “He is very big now,” whispered my Finnish friend Riitta, though I wasn’t sure if she was referring to his popularity or the fruits of success threatening to burst from beneath his cummerbund. But even if he did look a bit like Robbie Williams with five extra years and ten extra kilos, Jari gave ’til it hurt, squeezing every ounce of emotion from each song of love, loss and dreams of better times.

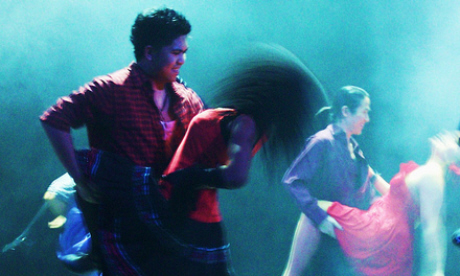

The dancing is a slightly less emotive affair. When Argentinian performers first brought the tango to Europe in the 1910s, the craze swept the continent over the next two decades, a torch picked up in Britain by bands with names like Geraldo and his Gauchos. But while the passion for tango waned elsewhere by the end of the 1920s, in Finland it took deeper root, undergoing a transformation which replaced sharp Latin athleticism with a slower, northern European, up-close shuffle – described memorably by one anonymous wag as “an Argentine tango with a bucket of water thrown on it”.

The 1950s saw an explosion in outdoor dancing as the Finns cast off their wartime cares. Dance pavilions (lavatanssit) sprang up in every village, and venues like Pavin Tanssilava in Vantaa, just outside Helsinki, remain popular summer attractions.

Like ballroom dancing in Britain, the tango is seen as largely a middle-aged thing. But it is still taught in Finnish schools along with perfect English and social responsibility, and even the youngsters who roll their eyes when you mention it, can usually name the Tango King and Queen crowned each year at Seinäjoki.

After cramming into a little hall in Seinäjoki with hundreds of locals for a lesson from tango legend Ake Blomqvist, and fortified with drink from the sprawling marquees that had sprung up in the town centre, I was ready for ‘Tango Street’. Here, no-one really cared if you had two left feet, though there was not actually enough space to try anything too flashy even if you knew how. Clutching fellow novice Amanda to my chest, we swept into the melée, shuffling convincingly enough to a procession of local bands beneath a midsummer sky that, even as midnight came and went, never lost its glint of blue.

Despite its northern European sophistication, Helsinki is not a tango-free zone, though attitudes to it are dismissive among the younger generation. “Tango is bollocks,” I was told by twentysomething Jani as we drank in hip central bar Fiba, where the local spirit Koskenkorva inspires more passion than a dance lacking in both beats per minute and cool associations. His friend Sami echoed the sentiment: “I know all the moves, but I hate it.”

Tango in Helsinki is an underground activity – literally, since the city’s tango Mecca is a basement dancehall, Vanha Maestro on Fredrikinkatu.

In the etiquette of tango it’s not the done thing to refuse a dance. But even if Finnish liberalism means women are technically able to ask for a dance anytime, most wait until the bandleader announces “Naistenhaku” (“Ladies’ choice”).

I had just one dance, my partner, like most here, past her first flush of youth. “When people turn 40 they suddenly want to tango,” she said, as I tried not to step on her toes. “It’s more popular in the countryside too.”

The next night I headed for the countryside. Lohjan Tanhuhovi is an hour out of Helsinki, a country dance-hall whose neon sign stood out in the twilit fields and pine forests.

My initial impression was of a set from a Scandinavian Twin Peaks, without the damn fine coffee but with the same air of a world slightly out of kilter.

There are dance halls like this all around Finland. Over the entrance the word Hummpasali in big letters sounded like ribald acknowledgement of the city slickers’ sneers about tango halls being more about pick-ups than dancing – though it turned out that hummpa was simply a Finnish cross between a waltz and a foxtrot.

A line of men, alone or in small groups, stood up one wall, gazing across a wide dancefloor at seated tables of women along the opposite wall. On stage, a combo glorying in the name Markus Tormala & FBI Beat belted out numbers for dancers who ebbed and flowed to a pattern I couldn’t even begin to grasp.

I watched, impressed, as a huge-bellied farmer belied his girth, gliding lightly around the floor with a succession of partners curved uncomplainingly around his paunch, proof perhaps that sometimes grace really can be more important than looks. Meanwhile a fashion parade of styles not seen in Britain since the early 70s swept by in the warm yellow light, to the amazement and amusement of the women in my group. “The only time I’ve ever seen anything like this was at the Rose of Tralee festival,” muttered Irish Eileen in awe-struck tones.

Locals come from as far as 50km away to dance here on a Saturday, I learned as I danced with Marjatta. A vivacious blonde pushing towards her mid-century, dancing is a passion that Marjatta has suffered for. “I broke my back,” she revealed, “doing the paso doble on a slippery floor.” We twirled with extra care, adding to the modicum of grace for a couple more dances before I resumed my position as visiting wallflower, watching as couples moved in time to the slow spinning of the glitterballs above their heads.

The derision of the Helsinki smart set was still in my ears, but I thought they were missing the touching innocence of this search for closeness in the middle of a lonely northern night. What it lacked in style and Latin fire, perhaps it made up for with inhibitions lost, in a place of light and music.