How to avoid the packed-pubs of Dublin's streets and still get a taste of the city

"The floozy in the Jacuzzi? Aw, she’s long gone, deary.”

I was taken aback at the casual response to my query – my informant seemed strangely unmoved about the removal of one of Dublin’s best-known statues from outside the tourist information centre on O’Connell Street.

“They shifted her during the street redevelopment last year,” she explained. And it might have been my imagination, but I’m pretty sure I heard her mutter: “And good riddance, to be sure.”

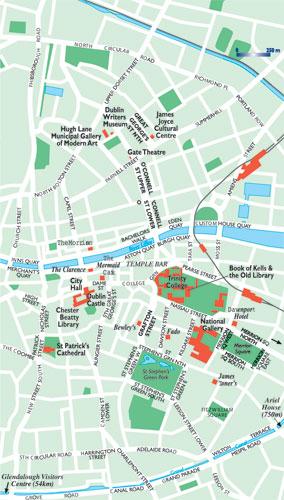

That was a blow. The avant-garde likeness of James Joyce’s character Anna Livia – alternative nickname: ‘The hooer in the sewer’ – was the last statue on my literary trail. Already I’d passed her creator just around the corner, admired Irish rights hero Daniel O’Connell overlooking the Liffey, spotted Molly Malone hawking those cockles and mussels on bustling Grafton Street and snapped Oscar Wilde’s sardonic smile as he lounged louchely in Merrion Square, looking for all the world like Hugh Grant sporting a garish velveteen smoking jacket.

But that final tick-box for poor, watery Anna remained unchecked.

As preparation for the annual theatre festival, the main reason for my visit, I’d made another ill-fated attempt to struggle through Ulysses, and had been struck by a comment made by Joyce’s protagonist, Leopold Bloom: ‘A good puzzle would be to cross Dublin without passing a pub’. How hard could it be, I’d wondered, to fill a weekend in Guinness Central without succumbing to the lure of the Liffey water – to avoid the Temple Bar stout-swilling hordes and spend a teetotal weekend in Dublin?

It’s a little over 15 years since an injection of EU funding set the so-called Celtic Tiger roaring – Ireland’s economic revival, accompanied by the makeover that came with Dublin’s term as European City of Culture in 1991. The regeneration (some might say sterilisation) of large swathes of the capital has been notoriously both a boon and a bane, but there’s no doubt that Dublin’s cultural life has been enriched by the foundation and refurbishment of museums, galleries and arts projects. Joining the dots of the city’s literary legacy seemed as good a way as any of scratching beneath the newly polished surface.

At the beginning, of course. Forget Swift, Wilde or Shaw – the most important book in Dublin was produced by early-9th-century monks who fled to Kells from the small Scottish isle of Iona. The Book of Kells, a wonderfully illuminated Latin copy of the gospels, has graced Trinity College since the 17th century; the accompanying exhibition traces the history of Irish writing, from Ogham script carved into standing stones through to the production of early Christian manuscripts.

Stepping into the college precincts from the early morning traffic crowding College Green, Trinity is an oasis of calm presided over by the 30m-high Campanile, shading the students draped across the kempt lawns of Library Square. This is the made-up face of Dublin, rubbing shoulders with the gentrified centre of the southside: the shopping strands around Grafton Street and St Stephen’s Green, the highbrow appeals of the Nationals (Gallery, Museum and Library), and the pride of Dublin’s Georgian architecture.

Around Oscar’s perch, the railings hemming Merrion Square act as makeshift market stalls for artists’ wares – if you can’t afford a grand Georgian townhouse, perhaps a watercolour of the original might suit your pocket better.

I crossed the river at photogenic Ha’penny Bridge near Temple Bar – steering clear of the boozers, naturally – before heading east. North of the Liffey, the commercial artery of O’Connell Street leads to Parnell Square, an artistic boxing ring where the heavyweights of the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art and the Writers’ Museum gaze haughtily across at the elegant Gate Theatre. Built in the late 18th century and opened as a theatre in 1929, the Gate continues to stage the most impressive plays with big-name actors: Orson Welles and James Mason gave early performances here.

As I moved away from O’Connell Street, the Georgian houses became a little more faded and frayed around the edges. It’s in this transition zone that Joyce lived for a time as a lad, and it’s here I found the James Joyce Cultural Centre; more than just a tribute to the author, the restored townhouse recreates a slice of old Dublin. Joyce himself left the city in his early 20s and spent much of his life in self-imposed exile in mainland Europe – he considered Dublin society to be stifling, provincial and tedious. I began to wonder what he’d make of today’s vibrant cultural life.

Thirsty work, walking. Back on the southside, James Toner’s boasts flagstoned floors, tiny snugs and drawers for tea and groceries behind the bar – the kind of traditional pub that looks almost too traditional, as if it’s been carefully designed to appear ‘authentic’.

But this is the real deal: pictures of Peter O’Toole draped across the doorway demonstrate that it was one of the hellraiser’s favourites, and also allegedly the only pub WB Yeats drank in. I didn’t need the displays in the Writers’ Museum to remind me that most of Dublin’s finest wordsmiths enjoyed a pint or three to oil the creative processes – surely justification for inclusion on a literary trail? Sláinte.

When to go: Dublin is a buzzing destination at any time of year, although winter tends to be cold and wet, and some visitor attractions close between October and March. Summer weekends (and St Patrick’s Day) get very busy, and accommodation fills up quickly; late spring and early autumn are ideal times to visit, when the weather’s warm and crowds are smaller.

Festivals: There’s a wealth of festivals year round; one of the biggest is St Patrick’s Festival in mid-March, when a programme of street theatre, music, exhibitions and fireworks culminates in a parade from noon on St Patrick’s Day (17 March).

Guided walks and plays are organised for Bloomsday (16 June) to celebrate the journey of the hero of Ulysses.

Irish dance, music and food are celebrated at the Dublin Irish Festival in early August.

The Dublin Fringe Theatre Festival overlaps with the renowned Dublin Theatre Festival , from late September to mid-October, which attracts respected actors and directors as well as breakthough works.

From May to August, events of all descriptions are held at various venues throughout Temple Bar during the Diversions contemporary arts festival .