Tektite 1, shown here in an artist's depiction, was an early experiment in long-term underwater living in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Tektite 1, shown here in an artist's depiction, was an early experiment in long-term underwater living in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

The city of San Francisco extends to the Pacific, but its varied terrain does not, in fact, stop at the water’s edge. Of course, no street or sidewalk can reach the shoals and unexplored reefs of the vast seabed west of the coastline. But what if there were a way to access this picturesque marine terrain of underwater canyons and escarpments?

This is the hope of a speculative “sub hub”—short for submarine hub—under discussion at San Francisco’s Aquarium of the Bay. Brian Baird, Director of the Coast and Ocean Program for the Aquarium, described the proposed expeditionary submarine network as a way to bring everyday San Franciscans, tourists, and “citizen scientists” out into the marine deep, expanding their understanding of San Francisco’s larger ecological context. Distant seamounts would become as easy to visit—and as much a part of the region’s established geography—as the Golden Gate Bridge or Muir Woods.

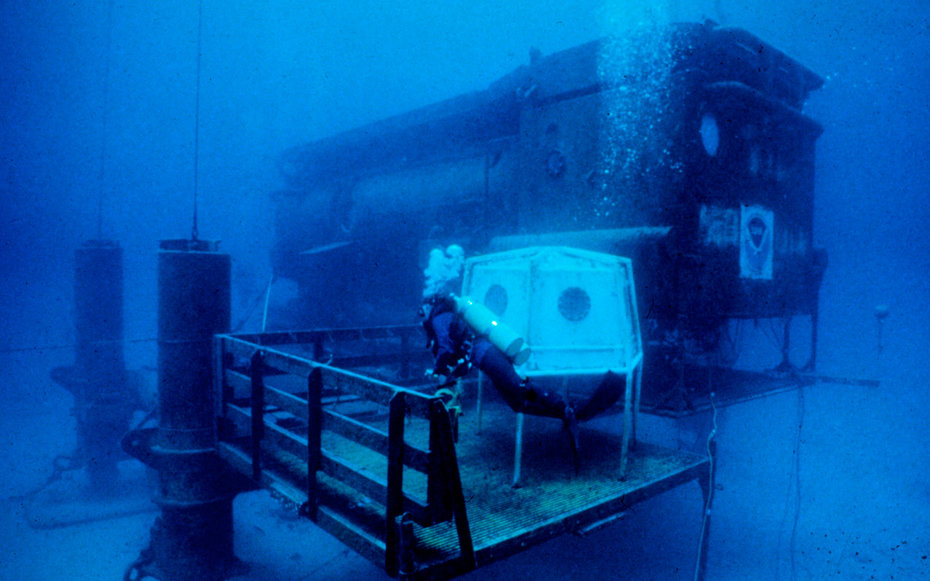

The Aquarium is developing the project in collaboration with legendary undersea explorer and scientist Sylvia Earle, who helped pioneer intensive marine research work, leading to roles as chief scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence. She also mastered the elusive art of living beneath the waves. In 1970, Earle and a small team of female oceanographers took up residence in an underwater laboratory known as Tektite I in order to study the biological processes of coral reefs. More recently, she explored the possibilities of long-term human existence below the surface at the Aquarius Reef Base off the coast of Florida.

As author Ben Hellwarth explains in his excellent 2012 book Sealab: America's Forgotten Quest to Live and Work on the Ocean Floor, these experiments were themselves part of a larger initiative to discover the physiological and psychological effects of dwelling for extended periods of time in an enclosed world of pressurized chambers and stale air. Aquanauts, as they were often described, investigated the possibilities of human life not on faraway moons and planets but within the alien landscapes hidden just beyond the coastal horizon.

Of course, visions of aquatic settlements and even entire underwater cities have long been a staple of science fiction. They are usually presented either as industrial projects, such as deep-sea mining firms, or as political utopias, hopeful experiments in alternative living that carry an aura of ecological responsibility. In the 1960s and 70s, these idealized marine aspirations began appearing in architectural proposals, such as Ant Farm’s tongue-in-cheek but conceptually provocative “Dolphin Embassy” project. Conceived as an arena for cross-species communication, the embassy was to be a spatial interface that would transform humans and dolphins alike into ambassadors of their species.

Of course, underwater restaurants and even fully submerged hotels are already a reality. These luxury developments aren’t born out of the scientific inquiry that animates Earle’s work or the projects documented by Hellwarth’s book, but they are still useful as proofs of concept: the technology does exist. On a purely technical level, the idea that San Francisco could have underwater settlements west of the Golden Gate, connected not by subways but by submarines, is not entirely outlandish.

So would the sub hub at the Aquarium by the Bay mean that our grandchildren might be able to look forward to a future of pressurized domes and modular villages beneath the waves of the Pacific? Well, not quite—at least not as the plan now stands. The project would serve only as a terrestrial headquarters for brief out-and-back expeditions into the surrounding expanses. These guided submarine trips would be both touristic and scientific in nature, Baird explained to me, specifically highlighting such areas as the Farallon Escarpment, the Rittenberg Bank, and various seamounts and canyons, all within the space of an afternoon trip.

To help develop a more concrete vision of the sub hub itself, the Aquarium has been consulting with noted architects William McDonough + Partners on an overall master plan that would be both environmentally sound and sustainably powered. But the design of the facility itself will have to wait. There’s still a lot of fundraising to do.