Morning at Playa Flamingo. Photo © Linda Seid Frembes, licensed Creative Commons Attribution No-Derivatives.

Guanacaste has been called Costa Rica’s “Wild West.” The name Guanacaste derives from quahnacaztlan, a word from an indigenous language meaning “place near the ear trees,” for the tall and broad guanacaste (free ear or ear pod) tree that spreads its gnarled branches long and low to the ground; during the hot summer, all that walks, crawls, or flies gathers in its cool shade in the heat of midday. The country’s first national park, Santa Rosa, was established here, the first of more than a dozen national parks, wildlife refuges, and biological reserves in the region.The lowlands to the west comprise a vast alluvial plain of seasonally parched rolling hills broadening to the north and dominated by giant cattle ranches interspersed with smaller pockets of cultivation. To the east rises a mountain meniscus—the Cordillera de Guanacaste and Cordillera de Tilarán—studded with symmetrical volcanic cones spiced with bubbling mud pits and steaming vents. These mountains are lushly forested on their higher slopes. Rivers cascade down the flanks, slow to a meandering pace, and pour into the Tempisque basin, an unusually arid region smothered by dry forest and cut through by watery sloughs. The coast is indented with bays, peninsulas, and warm sandy beaches that are some of the least visited, least accessible, and yet most beautiful in the country. Sea turtles use many as nurseries.The country’s first national park, Santa Rosa, was established here, the first of more than a dozen national parks, wildlife refuges, and biological reserves in the region. The array of ecosystems in the region ranges from pristine shores to volcanic heights, encompassing just about every imaginable ecosystem within Costa Rica.

No region of Costa Rica displays its cultural heritage as overtly as Guanacaste, whose distinct flavor owes much to the blending of Spanish and indigenous Chorotega cultures. The people who today inhabit the province are tied to old bloodlines and live and work on the cusp between cultures. Today, one can still see deeply bronzed wide-set faces and pockets of Chorotega life.

Costa Rica’s national costume and music emanate from this region, as does the punto guanacasteco, the country’s official dance. The region’s heritage can still be traced in the creation of clay pottery and figurines as well. The campesino life here revolves around the ranch, and dark-skinned sabaneros (cowboys) are a common sight. Come fiesta time, nothing rouses so much cheer as the corridas de toros (bullfights) and topes, the region’s colorful horse parades. Guanacastecans love a fiesta: The biggest occurs each July 25, when Guanacaste celebrates its independence from Nicaragua.

Guanacaste’s climate is in contrast to the rest of the country. The province averages less than 162 centimeters (64 inches) of rain per year, though regional variation is extreme. For half the year (Nov.-Apr.) the plains receive no rain, it is hotter than Hades, and the sun beats down hard as a nail, although cool winds bearing down from northern latitudes can lower temperatures pleasantly along the coast December-February. The dry season usually lingers slightly longer than elsewhere in Costa Rica. The Tempisque basin is the country’s driest region and receives less than 45 centimeters (18 inches) of rain in years of drought, mostly in a few torrential downpours during the sixmonth rainy season. The mountain slopes receive much more rain, noticeably on the eastern slopes, which are cloud-draped and deluged for much of the year.

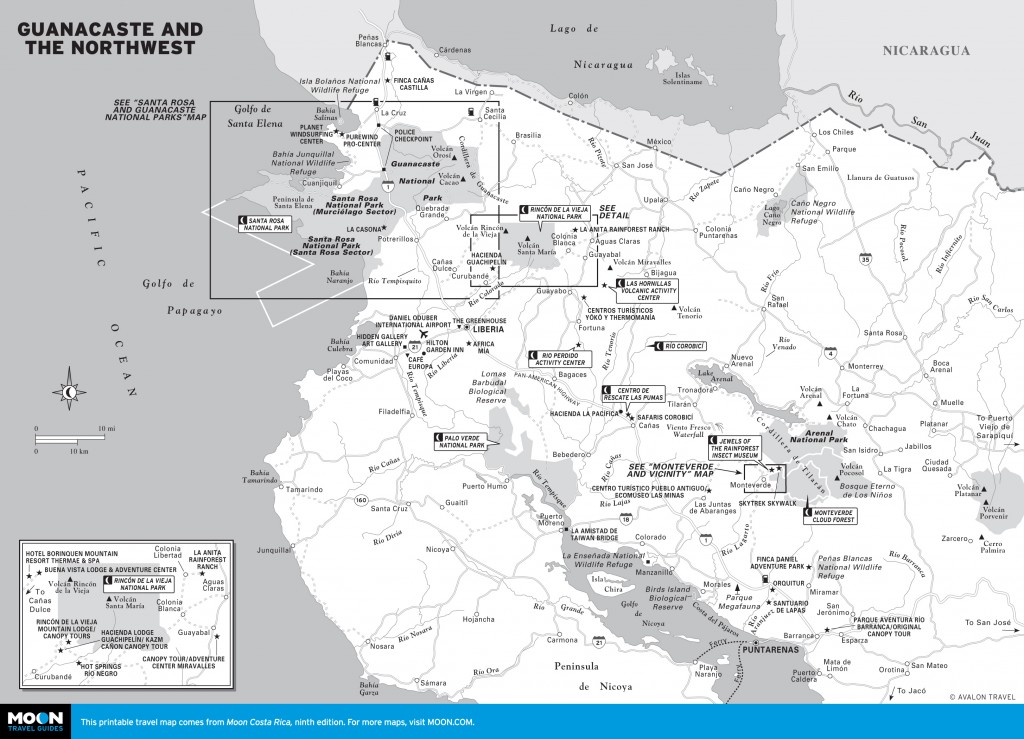

Guanacaste and the Northwest

The Guanacaste-Nicoya region was the center of a vibrant pre-Columbian culture: The Chorotega celebrated the Fiesta del Maíz (Festival of Corn) and worshiped the sun with the public sacrifice of young virgins. Descended from the Olmec of Mexico, they arrived in the area around the 8th century and soon established themselves as the most advanced group in the region. Their culture was centered on milpas (cornfields). Many of the stone metates (small stool-like tables for grinding corn) on display in the National Museum in San José are from the region.

The Chorotega were particularly skilled at carving jade and achieved their zenith in the craft between the 1st century BC and the 5th century AD. Blue jade was considered the most precious of objects. Archaeologists, however, aren’t sure where the blue jade came from. There are no known jade deposits in Costa Rica, and the nearest known source of green jade was more than 800 kilometers (500 miles) north in Guatemala.

The region was colonized early by the Spaniards, who established the cattle industry that dominates to this day. Between 1570 and 1821, Guanacaste (including Nicoya) was an independent province within the Captaincy General of Guatemala, a federation of Spanish provinces in Central America. The province was delivered to Nicaragua in 1787, and to Costa Rica in 1812. In 1821, when the Captaincy General was dissolved and autonomy granted to the Central American nations, Guanacaste had to choose between Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Rancor between Liberians, cattle ranchers with strong Nicaraguan ties, and Nicoyans, who favored union with Costa Rica, lingered until a plebiscite in 1824. Guanacaste officially became part of Costa Rica by treaty in 1858.

Guanacaste is a large region; its numerous attractions are spread out, and getting between any two major areas can eat up the better part of a day. The region is diverse enough to justify exploring it in its entirety, for which you should budget no less than a week. Monteverde alone requires a minimum of two days, and ideally four, to take advantage of all that it offers. Nor would you want to rush exploring Parque Nacional Rincón de la Vieja, requiring two or three nights.

Recent years have seen a boost in regional tourism following expansion of the international airport at Liberia, now served with direct flights by most key U.S. carriers. The airport is well served by car rental companies.

The Pan-American Highway (Hwy. 1) cuts through the heart of lowland Guanacaste, ruler-straight almost all the way between the Nicaraguan border in the north and Puntarenas in the south. Juggernaut trucks frequent the fast-paced and potholed road, which is one lane in either direction. Drive cautiously! Fortunately, in early 2013 work was well advanced to add a second lane in each direction along much of the route. North of Liberia, the route is superbly scenic. Almost every sight of importance lies within a short distance of the highway, accessed by dirt side roads. If traveling by bus, sit on the east-facing side for the best views.

Touristy it might be, but Monteverde, the big draw, delivers in heaps. Its numerous attractions include canopy tours, horseback riding, and art galleries along with orchid, snake, frog, and butterfly exhibits. At Selvatura, the one-of-a-kind Jewels of the Rainforest Bio-Art Exhibition is worth the arduous uphill journey to Monteverde in its own right. Most visitors come to hike in the Reserva Biológica Bosque Nuboso Monteverde (Monteverde Cloud Forest Biological Reserve), the most famous of several similar reserves that make up the Zona Protectora Arenal-Monteverde (Arenal-Monteverde Protected Zone).

Back in the lowlands, the town of Cañas offers Centro de Rescate Las Pumas and the Río Corobicí: the former a refuge for big-cat species, the latter good for relatively calm white-water trips. To the north, few visitors make it to Volcán Miravalles, where several recreational facilities take advantage of thermal waters that also feed bubbling mud-pots and geysers. Chief among them are the Las Hornillas Volcano Activity Center and Río Perdido Activity Center. A side trip to Parque Nacional Palo Verde, with more than a dozen distinct habitats, is recommended for bird-watchers. Nearby, Liberia is worth a stop for its well-preserved colonial homesteads. The city is gateway to both the Nicoya Peninsula and Parque Nacional Rincón de la Vieja, popular for hikes to the summit and for horseback rides and canopy tours from nature lodges outside the park.

Parque Nacional Santa Rosa is more easily accessed from the Pan-American Highway and is popular for nature trails offering easy viewing of a dizzying array of animals and birds. It also has splendid beaches, great surfing, and La Casona, a historic building considered a national shrine.

Visit Puntarenas, the main town, solely to access the ferry to southern Nicoya, or perhaps for a cruise excursion to Isla Tortuga. The Cámara de Turismo Guanacasteca (tel. 506/2690-9501), the Guanacaste Chamber of Tourism, is a good resource.

Excerpted from the Ninth Edition of Moon Costa Rica.