At the shore in Costa Rica’s Parque Nacional Corcovado. Photo © Miguel Vieira, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

The Osa Peninsula

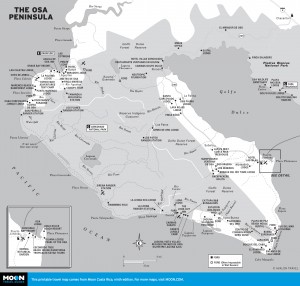

Costa Rica’s southwesternmost region is a distinct oblong landmass, framed on its east side by the Fila Costeña mountain chain and indented in the center by a vast gulf called Golfo Dulce. Curling around the gulf to the north is the mountainous hook-shaped Osa Peninsula and, to the south, the pendulous Burica Peninsula. North and south of the gulf are two broad fertile plains smothered by banana and African date palm plantations—the Valle de Diquis, to the northwest, separating the region from the Central Pacific by a large mangrove ecosystem fed by the Río Grande de Térraba, and the Valle de Coto Colorado, extending south to the border with Panamá.Nature lovers with a taste for the remote and rugged will be in their element. Star billing goes to the Osa Peninsula, smothered in a vast tract of pristine rainforest filled with the stentorian roar of howler monkeys, the screeches of scarlet macaws, and the constant dripping of water. Much of the jungle—a repository for some of the nation’s greatest wildlife treasures—is protected within a series of contiguous parks and reserves served by remote jungle lodges.

The region is the largest gold source in the country, as it has been since pre-Columbian times. In the early 1980s gold fever destroyed thousands of hectares of the Osa forests: The physical devastation was a deciding factor in the creation of Parque Nacional Corcovado. Rivers such as the Río Tigre and the Río Claro still produce sizeable nuggets; former gold miners have turned to ecotourism and today lead visitors on gold-mining forays.

The waters of the Golfo Dulce are rich in game fish, and the area is popular for sportfishing. Whales occasionally call in, and three species of dolphin—bottle-nosed, black spotted, and spinner—frolic in the gulf, which is charged by luminescent microbes after sunset. Although the gulf is protected and relatively calm, surfers flock for the waves that wash the southeast tip of the Osa Peninsula and push onto the beaches of the Burica Peninsula, where indigenous communities exist in isolation in the mountains. Offshore, west of Corcovado, is craggy, desolate Isla del Caño, and way, way out to the southwest is the even more desolate Isla del Coco, an island whose surrounding waters are a venue for some of the world’s finest diving.

This is one of Costa Rica’s wettest regions. Be prepared for rain and a lingering wet season: the area receives 400-800 centimeters (160-315 inches) of rain annually! Violent thunderstorms move in October-December.

The indigenous peoples of this zone had historical links with South America, and the region was already a center of gold production when Europeans arrived in the early 1500s. Pre-Columbian goldsmiths pounded out decorative ornaments and used a lost-wax technique to make representations of important symbols, including crocodiles, scorpions, jaguars, and eagles.

Spaniards searched in vain for the legendary gold of Veragua and thereafter forsook the inhospitable region for the more temperate terrain and climate of Guanacaste and the central highlands.

A unique and ubiquitous element of the region is the perfectly spherical granite balls (bolas or esferas de piedra) that range from a few centimeters to three meters across and weigh as much as 16 tons. They litter the forest floors and have been found in groups of as many as 25. No one is certain when they were carved or how, or for what purpose, although it is probable that they had religious or ceremonial significance. The spheres and gold ornaments dating back to AD 400-1400 provide the only physical legacy of the indigenous Diquis culture.

Most towns in the region were born late in the 20th century, spawned by United Fruit Company, which established banana plantations here in 1938 and dominated the regional economy until it pulled out in 1985.

Many visitors come to visit Parque Nacional Corcovado or Drake Bay, and fly out after a brief two- or three-day stay. You’ll shortchange yourself with such a limited trip; allow at least a week.

Scheduled air service is offered to Ciudad Neily, Drake Bay, Palmar, and Puerto Jiménez (you can also charter flights to Corcovado), and Jeep taxis and local tour operators offer connecting service to almost anywhere you may then want to journey. If you’re driving yourself, a 4WD vehicle is mandatory to negotiate the dirt roads of the Osa Peninsula and the Burica Peninsula. In wet season, the road to Corcovado can prove impassable to even the largest 4WD vehicles.

Accommodations tend to cater to nature lovers: take your pick from safari-style tent-camps to deluxe eco-lodges. Dozens of nature lodges line the western shores of the Osa Peninsula and the contiguous Piedras Blancas, while beach options that primarily draw surfers and the student crowd tend toward the budget end of the spectrum.

Highway 2 (the Pan-American Highway) cuts a more or less ruler-straight line along the base of the Fila Costeña mountains, connecting the towns of Palmar (to the north) with Ciudad Neily and Paso Canoas (to the south), on the border with Panamá. The towns offer nothing of interest to travelers, other than as way-stops in times of need.

Sierpe, a port hamlet in the middle of African date palm plantations north of the Osa Peninsula, is the starting point for boat forays into the Humedal Nacional Térraba-Sierpe wetlands reserve and to Drake Bay, the only community on the western side of the Osa Peninsula. Drake Bay has some splendid accommodations for every budget and particularly caters to sportfishers and divers. If you’re planning on visiting Isla del Caño, you’ll typically do so from here. A coast trail provides access to Parque Nacional Corcovado, which offers some of the finest wildlife-viewing in Costa Rica (local lodges also ferry guests to Corcovado by boat). Tapirs are relatively easily seen, and jaguar sightings— while rare—are as likely here as anywhere else in the country.

The main gateway to Corcovado is Puerto Jiménez, which caters to the surfing and backpacking crowd but is broadening its appeal with sportfishing lodges and accommodations at nearby Playa Platanares. This beach has an enviable setting adjacent to a mangrove ecosystem harboring crocodiles and all manner of wildlife. Centrally located Puerto Jiménez makes an ideal base for exploring the region; water taxis connect with the laid-back surfing beach communities of Zancudo and Pavones, and the otherwise hard-to-reach beaches of Golfo Dulce, where the Casa Orquídeas and Osa Wildlife Sanctuary are must-visits.

Although it is pulling itself up by its bootstraps, Golfito, the only town of any size, can be given a wide berth; this port town holds little attraction except as a gateway to the little-visited Refugio Nacional de Vida Silvestre de Golfito (there are better places to spot wildlife) and as a base for sportfishing forays and journeys by dive-boat to Isla del Coco, famous as a world-class dive site.

Excerpted from the Ninth Edition of Moon Costa Rica.