Looking towards Isla Santa Clara from the airfield. Photo © Pato Novoa, licensed Creative Commons Attribution.

In his classic 1830s seafaring adventure Two Years before the Mast, Richard Henry Dana called remote Isla Masatierra “the most romantic spot of earth that my eyes had ever seen.” Dana’s impression owed much to novelist Daniel Defoe, who had placed fiction’s famous castaway Robinson Crusoe in the Caribbean, but the real-life Crusoe was Alexander Selkirk, a Scotsman marooned more than four years on a tiny but mountainous island several hundred kilometers off the South American coast.In what is now almost entirely national park land, visitors to what is now called Isla Robinson Crusoe, in what is now part of Chile, can hike to Selkirk’s lookout through forests of rare endemic plant species and observe endangered fur seal colonies in local launches. Air access from Santiago is easy (if expensive) and there’s an infrequent maritime connection with Valparaíso.

Isla Robinson Crusoe

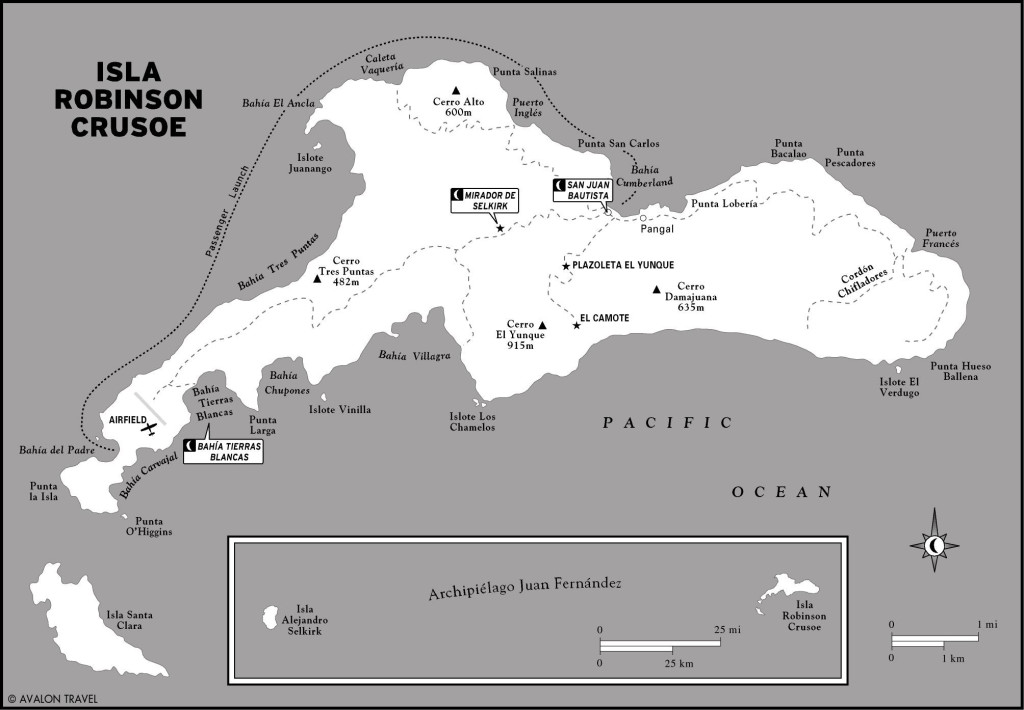

Almost directly west of Valparaíso, 667 kilometers from the continent, three subterranean mountains break the Pacific surface to form the Archipiélago de Juan Fernández. The only permanently inhabited one is Isla Robinson Crusoe (ex-Masatierra). Isla Santa Clara (known to early buccaneers as “Goat Island”) is just a few kilometers off its southwesterly tip, while Isla Alejandro Selkirk (ex- Masafuera) is 167 kilometers farther west. The original Spanish names are geographical references: Masatierra means “closer to land” (the South American continent); Masafuera means “farther out.”

All are mere dots in the Pacific: Robinson Crusoe’s area is only 93 square kilometers, Santa Clara’s only 5 square kilometers, and Alejandro Selkirk’s only 85 square kilometers. And all are ruggedly mountainous: Robinson Crusoe’s Cerro El Yunque rises 915 meters above sea level; Alejandro Selkirk’s Cerro Los Inocentes reaches 1,480 meters; and even tiny Santa Clara sticks 375 meters above the sea. Because the islands are so small—Robinson Crusoe is 22 kilometers long and only 7.3 kilometers wide—the terrain is even more abrupt than these modest elevations might suggest. Because it sits atop a subterranean mountain range, the land plunges swiftly into the Pacific depths.

In an area where subtropical Pacific seas blend with sub-Antarctic flows from the northerly Humboldt or Peru Current, the archipelago has a Mediterranean oceanic climate resembling that of Chile’s continental heartland. Temperatures are mild: On Robinson Crusoe, the annual average is 15.2°C, with an average summer maximum of 21.8°C and a winter minimum of 10.1°C. More than two-thirds of the 1,000 millimeters annual precipitation falls between April and October; less than 10 percent falls in the summer (Dec.–Feb.).

Rainfall statistics are misleading, though, because the steep east–west ridge of Robinson Crusoe’s Cordón Chifladores causes a strong rain-shadow effect. Its north side is verdant rainforest, while the south side and Isla Santa Clara are as barren as the Atacama coastline. Even then, like the Atacama, the arid south side gets convective fogs like the camanchaca (fog that forms on the Chilean coastline).

While a group of Australian and New Zealand archaeologists have sought evidence of a pre-Columbian presence on Juan Fernández, all the unusual items they found appear to have been from historic times. When Spanish navigator Juan Fernández named them the “Islas Santa Cecilia,” after the date of their sighting in November 1574, they were uninhabited, and they had no permanent residents until the mid- 18th century.

Even if there was no regular human presence on the islands until then, there was plenty of activity. Foreign navies and privateers regularly took R&R and filled their water casks here. Even after Spain finally founded the settlement of San Juan Bautista in 1750, North American sealers continued to slaughter the endemic Juan Fernández fur seal (Arctocephalus phillippi) for its valuable pelt.

The closest claim to permanent residence belonged to the impulsive Selkirk. In 1704, after continual quarrels with Captain Stradling of the privateer Cinque Ports, the irascible seaman demanded to be put ashore. Though he repented almost immediately, the departing Stradling rebuked him with the admonition “Stay where you are and may you starve!” Overcoming his initial despair, Selkirk endured more than four years in nearly utter isolation.

Masatierra was no tropical paradise but, fortunately for Selkirk, it was a temperate, partly manmade one. Wood and water were plentiful, wild cabbages abounded, and, most important, the Spaniards had introduced goats. These feral beasts, while inflicting incalculable damage on the native flora, provided meat and clothing for the solitary exile until his rescue, in 1709, by Commander Woodes Rogers of the privateers Duke and Duchess. Rogers, whose famous pilot William Dampier had earlier gone to sea with Selkirk, left a vivid description of his first sight of the castaway:

Immediately our Pinnace return’d from the shore, and brought abundance of Crawfish, with a man Cloth’d in Goat-Skins, who look’d wilder than the first Owners of them.

Returning to Scotland, Selkirk recounted his story to journalist Richard Steele and eventually it found its way into Defoe’s novel, though Defoe changed the location from the Pacific to the Caribbean.

In the decades after Selkirk’s return to Scotland, figures to visit Juan Fernández included Lord George Anson, who commanded the Royal Navy’s South American squadron during a nearly four-year circumnavigation of the globe and named the main anchorage Cumberland Bay. Spanish concerns about foreign interlopers led to the establishment of San Juan Bautista, at Bahía Cumberland, by midcentury, but it was mainly a penal colony. In 1814, during the wars of independence, the Spaniards sent 42 prominent political prisoners here.

Even the establishment of Chilean authority in the early 19th century made little difference, as Dana noted that:

All the people there, except the soldiers and a few officers, were convicts sent from Valparaíso…. The island… had been used by the government as a sort of Botany Bay.

Nor did it stop the exploitation of the island’s natural wealth: The valuable fur seal declined so rapidly that U.S. sealer Benjamin Morrell remarked, in an instance of either remarkable naïveté or transparent disingenuousness, that:

Perhaps the moral atmosphere may have been so much affected by the introduction of three hundred felons as to become unpleasant to these sagacious animals.

The islands came to world notice again in 1915 when the British navy, once again a factor in the South Pacific, forced the scuttling of the massive German cruiser Dresden. Two decades later, the Chilean government created the national park that, in 1977, became a UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve. The only parts of the island not part of the national park are the airfield and the village of San Juan Bautista, which relies on the high-value local lobster, flown to Santiago restaurants, and a modest tourist trade. San Juan’s shoreline suffered major damage from a tsunami triggered by the massive 8.8 earthquake of February 27, 2010.

Read more about the Parque Nacional Archipiélago Juan Fernández.×Excerpted from the Fourth Edition of Moon Chile.