The young western guy who goes to India seeking higher understanding of himself/mankind/god, only to discover worldliness and inexplicable suffering and confusion is an oft-repeated story. For the record I did not go to India expecting to find holiness. I went as a raw, naive, unimaginative, worldly-minded kiwi boy intending to climb mountains. India happened to lie on the route to the ridge-top of the Himalayas, where my intention was to stand on a pile of dead rock, a man truly alone, and be as far away from humanity, god and my own problems as I could possibly get. Here is one of the things that happened en route from Calcutta to Katmandu:

Delay en route to my hot date

Delay en route to my hot date

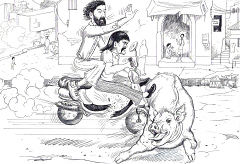

For some reason born of masochism and frugality, I had chosen to travel third class from Varanasi to Jaipur. On the map this is not such a long way. I boarded the carriage unfazed by the overcrowded, seatless, sun-heated space. Several hours later, when we had advanced only a few kilometers, and the occupancy of the carriage had increased about fivefold, I was feeling very different. I was drowning in people; the current of their movement crushed me in between the toilet stalls at the back; an undertow caught my backpack and sucked it away into the solid crowd. It took thirty hours to get to Jaipur, crushed in a torturous position among people clambering to relieve themselves, choking in fecal fumes, vomiting until my belly was empty, mourning the loss of all my possessions. The train would pause, inexplicably, for hours at a time in the middle of the Rajastani desert. At one station, there was a political demonstration going on. Rioters tried to get into the carriage by climbing through the windows. The other passengers, now as insane as I, beat them and threw them out again. When this stinking, contorted, baking hell came to an end, I was diminished in health and will, a factor that might help explain the miscalculations that followed. Staggering finally from my coffin of suffering, I was astounded when fellow passengers handed my lost backpack, flattened like a cardboard cutout. I entered the bustling streets of Jaipur, still nauseous and reeling. My path was suddenly blocked by a small, poorly attired man who greeted me with civil inquiries about my nationality, age, family size and profession. To the last question I replied, not untruthfully: 'I'm an artist' (It was the illustration of a children's book that paid for this journey). The man smiled with delight and responded: 'I too am an artist! Why don't you come to my studio and enjoy a cup of tea?' That I believed I had discovered a comrade in creativity will demonstrate the deterioration in acuity my mind had experienced. I happily accepted the invitation and followed my new friend around the corner. 'My brother,' the small man confided, 'is also an artist. I would like to introduce you to Swaran!' Whereupon the small man vanished, never to be seen again, as an immensely tall, fat man in a superb white suit burst out of a door at me. He bore zero family resemblance to his predecessor. Swaran invited me into his 'Art Shop,' offering me deep-fried cakes and fruit. Sweet tea washed the dust from my throat, although it still hung in a cloud around my filthy clothes and pack. Swaran talked at great length, pointing out the artwork hung from the walls, paintings on silk in the Rajastani courtly style: kings hunting tigers on elephant-back, processions of maidens, saints and warriors. By 'artist' Swaran meant that he was the owner of five actual artists. He kept them in a shed at the back of his house. Each one painted the same picture over and over. The same arrangement of dots on the deer's forehead, the same brush-strokes for the prince's profile. My fascination with this industrialisation of art soon gave way to annoyance as Swaran insisted that I buy a dozen or more from him. Out of sheer exhaustion, I agreed to purchase three, whereupon he pointed out that I would be a fool not to buy into his gemstone exporting business. With difficulty, I refused this business offer and left the art shop, hefting my pack in search of a hotel. Within a minute, my path was suddenly cut off by a small burly man my own age riding a yellow scooter. He had a thick greasy mullet, the moustache of a Mexican bandit (or my car-dealer uncle) and an Indian movie-star's rhinestone-covered shirt. In a gravelly, menacing voice, he demanded: 'Why do foreigners always tell me to f**k off?' His name was Rama. I listened sympathetically to his story. He was a student of languages who that afternoon had approached an Italian couple in order to practise his English. This – these expletives! – had been the reward for his thirst for knowledge. I reassured him that the Italians had probably not meant it personally. Perhaps they had had a bad day? Rama said gloomily: 'Many people, they look at my hair, my easy-style jean-pants, they think: Ah! This one is funky junky punky. You, do you think so?' I assured him that I didn't think he was funky junky punky. But I was eager to get to a hotel. He expressed his appreciation for my kind words, and assured me that I was already like a brother to him. Then he said: 'What were you doing in Swaran's shop?' When I told him about the paintings, and offer of gemstone-related business, Rama let out a low whistle of terror. He said: 'Swaran is a bad man, the worst man in Jaipur! He asks many foreigners to take out stones for him. When they refuse, he has drugs put in their baggage. Then the police arrests them!' He went on and on, describing the various forms of Swaran's easily-provoked revenge. He spoke of a man cut open and firecrackers tossed into his stomach. I became immediately frightened, and also overwhelmed with relief that Rama had given me warning of my predicament. 'How can I get out of Jaipur?' I asked. Rama shook his head. 'Swaran's father owns all the taxis in the city. It is not possible for you to leave without him knowing where you are. Get on my bike – I will take you to a place where you will be safe.' A few seconds later, pack on my back, perched three heads higher than my chaffeur, I found myself hurtling through Jaipur traffic. Rama drove like the craziest maniac I had ever seen before or since. He cut off trucks, weaving across the road between oncoming cars, bicycles, camels, cars, buses, handcarts, oxen, goats and other lunatic motorcyclists, all of them rocketing to their destinations in the same suicidal, double-guessing interwoven river-of-death fashion I was to see too often in the next few days. Rama me to a tiny hotel beside the city's mosque, where I fell asleep instantly in a cell-like room. My dreams were a meatgrinder of impressions from the last few weeks: human corpses barbecuing beside the Ganges, Sikkimise Tibetans drag-racing through a crowded market, limbless babies lying in rows beside a begging bowl outside the door of a cafe. When I awoke and stumbled out to the central courtyard, Rama was waiting there on his scooter, scowling through his moustachios and Four Square smoke. He insisted I accompany him on an evening tour of Jaipur. It seemed churlish to refuse, so I allowed myself to be rocketed, as if by magic carpet, to the ancient crumbling palaces that covered the desert mountains beneath a firmament of stars bright as the spear tips of a ghost army. Cattle grazed in the gutted hallways of the great pleasure domes of the Shahs. Beggars peeped out of windows once filled with stained glass. Camels defecated on the steps where kings once passed. In his guttural voice, Rama would produce a succinct summary of an empire before zooming off on the next kamikaze leg of our tour, scornfully dodging horses and jeeps, short-cutting through fields of scree, across the subsistence crops of peasants, through the centre of religious processions and military parades until, at last, the walls of the Pink City returned to view. This was when I met Jamal, whom Rama introduced as his 'brother.' It took a while before I realised that their brotherhood was of a similar nature to that of Panama-suited Swaran and his dhoti-clad underling. While Rama was as unpolished as a lump of granite, Jamal was the epitome of the wealthy young Indian gentleman of leisure, finely dressed and coiffured, well-spoken, in every way polished to a high patina. He was, by way of trade, a gemstone dealer. The only imperfection in his otherwise urbane aspect was the absence of a right forefinger, which appeared to have been lost to heat and friction, rather than a sharp edge. It took a while before I realised that Jamal was the brother in question, for I met about a dozen Rajasthani men at the same time, on the rooftop of the Green Tiger Silk and Jewel Emporium. I brought a couple of bottles of whisky to the occasion. As if by magic they vanished into the mouths of the other guests, before quickly reemerging in the form of songs, stories, expressions of joy and friendship. A youth in complete cricket uniform, with a scarred and dented face, was telling me about a cricket career cut short by a malicious googly, when Jamal interrupted the conversation to speak to me of far more important matters – namely, himself. I listened to wonder to his tales of womanising, moneymaking, world-travel and wheeler-dealing, a greenhorn rube soaking up the savvy of his sharper contemporary. And then Swaran swaggered onto the rooftop. Everyone drew back with a gasp, but his gaze was fixed directly on me. 'Mr Aaron,' he crooned with a ham's overstated delight, 'I thought that you might visit your good friend Swaran again, as you were invited to…' Rama's words of caution echoed in my head. It was like running into a warlord at the birthday party of his main rival. I began to offer idiotic, drunken excuses. I babbled something about bad news, my girlfriend dying of cancer, unhinged sanity and so forth. As he came up to console me with mock sympathy, the bitter grin still on his face, I remembered telling him earlier in the day that I did not have a girlfriend. A terrible silence had fallen on the rooftop as the others looked on, no doubt feeling genuinely embarrassed for the poor acting on both our parts. Then Jamal stepped forward and began yelling at the bigger man. For a few minutes they ranted and shook their fists at each other. Then Swaran turned and ran back down the steps. Jamal explained to me: 'Swaran feels that you insulted him by refusing to help him with his gemstone business. It is a big problem. He enjoys revenge more than money…' I said: 'I just spoke to the man for twenty minutes. Why would I want to get involved in such a stupid business?' Jamal shrugged. 'To export stones is not so stupid. You can make good money doing it, without any difficulty. All you need is a reliable man to work with. I am also, as I said earlier, a gemstone merchant…' When I woke the next morning I had a dim memory of having crammed numerous acts of high stupidity into a few hours. In my drunken state, I had been persuaded by Jamal and Rama to buy into their business. The deal's stick was the revenge of the insulted Swaran, from whom they swore to protect me until I could safely leave the city. The carrot was my own greed. I could make twenty thousand dollars by doing nothing more remarkable than delivering two boxes of stones to a man in Melbourne. The only investment required on my part was three hundred dollars, to cover the original cost of the goods. Somehow, at four in the morning, Rama had drunkenly driven me through the back mazes of Jaipur to wake up a money changer. With the required amount of rupees, we entered a part of town full of tottering, cracked thirteen-storey high rises, one of which was owned by Jamal. Inside this decaying tower, the walls had been knocked away to create long, low rooms in which hundreds of children sat in rows on each floor, facing each other across ten-metre long lathe axles. There was a grind-stone for each pair of children. Beside them were piles of rough stones, still with sand and dirt on them. One by one these stones would be applied to the grindstones with bare fingers, until shining facets were cut from the dull pebbles. A couple of lightbulbs lit each floor. In the half-darkness, sparks burst around us like fireworks. Rama led me from one row to the next, stepping over the sleeping forms of the children, stooping to pick out the finest stones before wrapping them in twists of newspaper. He gathered tigers eye, aquamarine, garnets, citron, lapiz lazuli and huge amounts of purple stone. They were big and chunky, cut as dowry jewelery for Indian women. As the adult supervisors passed packet after packet to Rama, I looked at the faces of the child-slaves – zombie-blank from lack of sleep – and their fingertips – bloodied from grindstone abrasions. Is this what had happened to Jamal's forefinger? And if he had been one of these workers, how had he got to the point of owning his own empire? My last memory of that long day was a visit to the post office. Rama persuaded (with the help of a three dollar bribe from me) a Sikh security guard with a shotgun to open the building and wake up a couple of postal workers sleeping under the desks. The stones were taped up into a small box, sewn up with calico and thick thread, secured with stamped red wax seals and covered with dozens of pais stamps before being placed into out-parcels. And that should have been that. When I woke up with a hangover, it was all too obvious that I'd been taken for a ride by everyone. My fear of Swaran, my greed for easy money, my weakness for liquor had done me out of three hundred bucks. It wasn't the end of the world. If I cut my losses and got out of Jaipur as soon as possible, I could get on with my travels. I would return to Australia and find out that the stones were fake and life would go on. But the simplicity of life is always tangled up by a woman. My plan was to head out of town that afternoon. Rama dropped by my hotel, ostensibly to say goodbye and share with me a newspaper cone of peanuts, chopped onion and chilli powder, but in reality to persuade me to buy another three hundred dollars worth of stones. In addition to this financial offer, he was pushing for me to give him my polar fleece, as a token of our deep friendship, and to prove that I didn't think he was a punky funky junky. Both offers I politely refused. But in the end, I was talked into delaying my departure for one more day, in order to attend the birthday party of the god Shiva, a festival being held in the middle of the Old City, with performances of famous local musicians, dancers, poets and puppeteers. Which required another death-defying scooter ride, during which I was almost stabbed through the face by a steel pole when Rama tried to overtake a scrap-wagon too closely. While he scouted around for extra floor space in the audience, I was given the task of parking his scooter, among a stand of about five hundred identical machines. As I set it on its kick stand, a group of a dozen young women in traditional dress suddenly confronted me. I began to explain to the first woman the innocence of my scooter-parking task when she interrupted with the friendly formalities of greeting. Where was I from? How old was I? Was I married? How many siblings did I have? What was my job? 'An artist?' she smiled. 'I too am an artist. I write articles for my university magazine. Would you like to come to my home for morning tea at eleven o'clock tomorrow?' I accepted the invitation, whereupon she inquired what I had done since my arrival in Rajasthan. Omitting all mention of gemstone smuggling, I named some of the sights Rama had taken me to, among them the mighty fortress built by Shah Jahan, a man who had once ruled the entire desert of Northwest India. Her face brightened at mention of the Shah's former residence, now the home of vultures and destitute families. 'He was my great-grandfather,' she said brightly. Her eyes had little Kohl on them, but they were long lashed and intense, and filled with a strange power that was impossible to understand. She asked: 'What is your religion?' What did I answer? I no longer remember. In those days, my faith in a Divine Law had been thrown hard. It was not any sorrow that had existentialised me, so much as the incomprehensibility of everything that was going on around me. Whatever my reply, she smiled: 'We are all Children of God. Look over behind the water tank.' She gestured at the sprawl of concrete that covered a steep rocky hillside with the complexity of an ant's nest. I followed the many-ringed finger of Shah Jahan's great-grand daughter, into the desert haze of the sky, half-expecting to see Shiva himself waving all his arms at me. 'That water tank' she went on. 'You see it? My house is behind that. My name is Meena Pareet. Can you remember that?' Her friend wrote it down for me and handed me the paper. 'You won't forget?' 'I'll be there,' I promised and Meena Pareet swept away, followed by her entourage of gold-saried fellow-princesses. I watched the performance in distraction, prancing clowns enacting tales from Hindu scripture, a mass of well-dressed people calmly clapping time to the music of strange instruments, bearded priests reading verses from enormous books. I had not spoken to a woman for over a month, I realised. What was the meaning of my meeting with this beautiful Rajasthani nobelwoman? Why had she spoken to me at all? From my brief glimpse into those depthless eyes, I had seen she was a being of matchless spiritual purity and physical perfection. I was overjoyed by the wonderment of it all. When Rama had succeeded in persuading another friend of his to put down his whisky bottle and stop dancing on people's hands and feet, I told him of the brief meeting, and my date for the following day, realising even as I spoke that my postponed departure would give him an opportunity to press his plans on me. He did exactly that. Later, while swerving maniacally between a camel and a fuel truck, he harangued me in a single breath with the economic necessity of investing more money into the semi-precious stone export sector, the ethical necessity of giving me his jacket, and on a less strident note, the romantic necessity of a decent outfit to replace the stained, ripped, greasy clothes that I had been wearing continuously for many weeks now. At Rama's family home, I was loaned the costume of a swish young man-about-town: appallingly flared lycra cadmium-blue slacks and a butterfly-collared custard-yellow shirt with ('need this to look like the clever') a thick quiver of biros jammed into the top pocket. Recalling that I stood a foot taller than Rama himself and was wearing my alpine mountain boots, I looked like a complete idiot. The next day over a breakfast of oily cakes and over-sweetened tea, Rama yammered on and on about gemstones. This annoying talk he would intersperse with references to my jacket ('I need it for the Himalayas in a few weeks' I argued. 'This time of year the Himalayas are very warm!' he countered with a snarl). As the hour for my date grew nearer, I realised that I was being put into a bind. Now it was thirst for female companionship that was being used as leverage against me. I gave in, agreed to buy more stones (but quickly!) and the procedure at the stone-grinding house and the post-office was repeated. Thus, another three hundred dollars poorer, dressed like a clown, hanging onto the back of Rama's death machine, we rocketed to the water tank. It was on this journey that we had our first accident. A pig bounded out into the middle of the road – a gigantic boar covered in scars and wounds, probably from earlier acts of foolishness. With a God-almighty impact of steel into a boulder of solid pork that snapped Rama's machine in half, prow and stern, we were launched yelling over the highway, dodging oncoming maniacs on Enfields who were not only attempting to race each other around a taxi that was forced to brake (halfway) through overtaking a bus, but also weaving between a troop of old men on bicycles while swerving to avoid the persons of myself and Rama, plus two bouncing, spark-raising halves of a scooter and a concussed, but sprinting monster hog. It took Rama only ten minutes after this misadventure to drag the fragments of his scooter over to a small tin shack beside the dusty highway, where a man smeared entirely in ball-bearing grease miraculously and instantly welded it back into a living machine again. After paying less than a rupee for this, Rama took us off for our final destination. We whizzed up behind the hideous but herculean bulk of the water tank, finding ourselves in a maze of narrow steps, pathways through tunnels, ladders, and thousands of different dwellings, hovels packed tightly among mansions, huts, warehouses, factories and ruins, straight up the cliff face. Rama must have asked dozens and dozens of passerbys for information about Meena's house. Nobody had heard of her. 'Meena Pareet is a very normal name,' he grunted at me, fighting to contain his annoyance. 'You only have name?' 'That's all,' I replied. 'Just the name.' Incredibly, having been passed on from door to door and crowd to crowd, we actually found her. An old servant woman in white workclothes gestured me up the long, steep front steps of a large house squashed between the massive bulwarks of the support back of the water tank. 'I'll be down the bottom,' said Rama, and my joy at having found my muse was matched only by the joy that I may never have to see this manipulative rogue and his atomic scooter again. Having removed my shoes, I entered a massive room of crumbling grandeur, dominated at the far end by a massive shrine curtained in thick incense smoke, at the left side by an ancient but powerful-looking woman in white robes (of mourning?), Meena's mother, and at the right side the entire rest of her family, three slightly younger sisters and a middle aged man in a huge red turban. All smiled at me as Meena came forward to greet me, but otherwise watched the ensuing exchange in silence. 'Thank you for coming,' said Meena, no doubt wondering why the cuffs of my pants came halfway up my shins, and my shirt sleeves halfway up my sunburned hairy forearms. The servant brought us tea and cakes. We sat on small stools and she gestured to an enormous pile of photo albums. 'Look at these pictures,' she offered. I found myself being forced through page after page of wedding photos. It was Meena's older sister, now away living with her husband. A fortune had obviously been spent. There were dozens of bridegrooms riding white horses, waving ceremonial swords, piles of cash being burned, the happy couple sitting on massive thrones among crowds of rejoicing guests. 'You are not married?' Meena asked for the second time. 'No,' I said. 'Do you have any money from your country?' she asked. I looked through my moneybelt, but there was not even a single Antipodean coin. By way of weak joke, I handed her a local coin. 'A rupee?' she laughed politely. 'I do not need it. I have already have forty lakh of rupees.' Having just learned this term, I realised that she was indeed a wealthy young woman. I made small-talk, idiotic, clumsy chatter for a while. Soon she interrupted: 'You are an artist?' she reconfirmed. 'Can you draw me a picture, and send it?' She wrote down her address. 'What kind of picture?' She smiled shyly, slyly. 'Please draw me a Western man with an Indian wife,' she said. None of this was making any sense. It was too much like a fairy tale, far too much, right down to the lines and the costumes. The turrets out the window, the crow perched on a tree branch, peering in, were a backdrop painted on wood. Except that it was all real. Could a fairy tale be real? One thing that was real was a feeling of fear, of doom, thin and dark, trickling into my heart. What did I fear? My own clumsiness in her presence, the inevitability of my messing up this, along with everything else I had ever done? Or did I fear the greatness of the thing that was being offered me: Meena Pareet herself? There was no doubt that she was propositioning me, nor was there any doubt that it was solely because of my white skin, my potential wealth, a chance at escape, but the most certain thing of all was that it would be a good thing to have her as a wife. Was I imagining the heat that came off her, electricity combined with fire, something sharp as laserbeams in her glance? Sitting opposite her, drinking tea that was almost pure melted sugar, I found myself wondering if I feared the woman herself. I knew that I would never hold her in my arms, for the only way to do that would be through marriage. Soon I would stand up and leave the room. Later I would write to her. Probably, the postman would get lost trying to find her house. We would forget each other. So it would be all right. But when the time came to say goodbye it didn't feel right at all. We walked to the front door of the house, and I shook Meena Pareet's hand again, seeing her face as if for the first time while we spoke together for the last time. What was she thinking? Did she realise that her beauty was too frightening for my young eyes? Did she mistake my disorientation for dislike? I felt a terrible guilt as I turned my back on her and took my first step down the hillside, asking myself: What am I? Why am I feeling guilty about turning down a woman when I'm in the process of making money from child labor? Am I a fool or a monster? As these thoughts raced through my head, my shoulder clipped the lip of a tall clay water jar that had just climbed to the front doorstep, on the back of the old servant woman in white. Bent over beneath her burden, she had not seen me, and my sudden tap knocked her off-balance. With a cry of fright, she tumbled backward, dropping the clay jar. In horror, I watched the ancient creature bounce down the sheer declivity, her bare skeletal limbs kicking the air as she skimmed off the sharp angle of each step. Twenty metres below she landed in a heap, the clay jar impacting the dirt street a centimetre from her head. I bounded down the steps, all introspection swept away in the genuine fear that I had just killed her. But incredibly, she was on her feet by the time I reached her, already shouldering the jar. Neither vessel or woman appeared damaged. The only expression on her face was a grin of embarrassment. I began to apologise, but laughter from the top of the steps drowned out my voice. I turned, looking up at Meena's beautiful silhouette as she said mirthfully: 'Don't worry, don't worry! She's only a servant!' The old woman began her climb again, calves like steel wires springing her from step to step. Turning, I hurried back down to see if I could get a lift with Rama.