I cracked my head on the roof and the shock absorbers groaned. It had been eleven years since I’d driven along this track, but it hadn’t changed. Meandering through the bush, the isolated cattle stockades and sticky clay pans gradually thinned out, giving way to deeper sand. Here the Land Rover steered itself along two deep, red ruts; tramlines across the Kalahari. It was slow going, but any faster than second gear hurt. Some corrugations bounced the whole vehicle as if it were on a piece of elastic; others rocked it forcefully from side to side. There was no choice but to take our time.

Around us the February air had been washed by yesterday’s rain. The vegetation was lush. Fresh shoots of Kalahari apple-leaf contrasted with the silvery sheen on the terminalia bushes, above a knee-deep carpet of shimmering grass that rolled into the distance. Bright pink devil’s claw flowers caught my eye, beside barbed fruits (now prized as a miracle drug in parts of Europe).

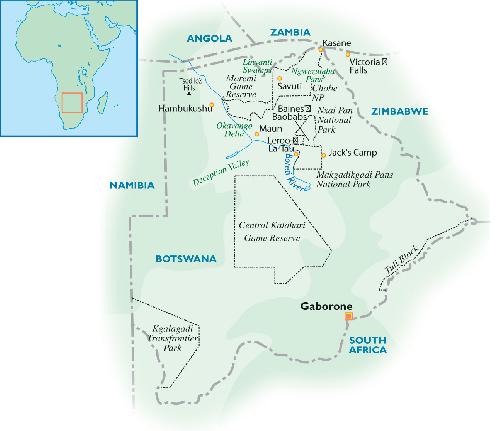

The vehicle’s gentle motion allowed our minds to wander. This was the middle of a long trip. We’d started at Victoria Falls, and then a few hours in a light aircraft took us to the lily-covered lagoons of the exclusive Kwara Reserve, in the Okavango Delta. Like virtually all of the private reserves in the Delta, this began as a trophy-hunting area beside Moremi Game Reserve. Gradually though, with the increase in camps for photographic visitors, hunting has been squeezed into more marginal areas, further from the parks. Botswana’s wildlife management has largely been successful, and its wild areas are expanding.

We’d had Kwara to ourselves for two gloriously sunny days. “Why don’t more people come in February?” our puzzled guide had asked. We spent that third afternoon reading, while a deluge of rain answered his question. But here the game never stops for the weather, so the following morning he had worked hard, using his vast experience and his keen eye for spoor, to track a pack of wild dogs. Northern Botswana has Africa’s strongest population of these endangered predators. They hunt by running down their prey over great distances, making them a challenge to follow. Finally we caught up with them when they stopped to devour an unfortunate impala. Bones and all, it was gone in a matter of minutes.

Jolting back to the present, we were shocked into stopping. A few metres ahead, brown lumps made of semi-digested twigs had been scattered across the track. Dry outside, wet inside; they were probably only a day or two old. Despite being 40km from water, deep in the Kalahari, we were amazed to realise that we were still in elephant country. Our concentration sharpened for the next few hours as we tried to avoid paranoia about surprised elephants terrorising our Land Rover.

The Kalahari covers most of central Southern Africa, extending far beyond the borders of Botswana, but it doesn’t have the spectacular Lawrence of Arabia dunes of the Namib. Instead it is a gently rolling sand-sheet where bushes and low trees grow on the sand of ancient fossil dunes. At the top of each low crest, we’d strain to look ahead, searching for elephants, landmarks – anything apart from greenery.

Eventually, growing with each successive dune-crest, the Tsodilo Hills rose up before us: a small group of rounded hills, standing proudly above the sands in the golden afternoon light. None are high; the tallest can be climbed in an hour. There is little big game here, and no shimmering lakes or rivers. Yet there’s nowhere in the whole Kalahari that seems as magical.

Years ago, I’d hitched through Botswana: two weeks on the back of an open pick-up, driven by a couple of Peace Corps teachers. We’d travelled through the game parks, sharing a dog-eared copy of The Lost World of the Kalahari by Laurens van der Post. In it he had described his search for the “survivors of Stone Age Africa” – the Bushmen. It was a lyrical account written in 1958, which inspired me and doubtless many others.

Two years after that trip, I visited the hills for the first time. It was 1990, just a few weeks after Namibia’s independence celebrations. I’d made a long diversion, but underestimated the time needed, leaving just a night to camp and less than a day to look around. Despite the rush, I left with a feeling of peace; a sense of having visited somewhere almost spiritual. I promised myself I’d return.

On this trip we could stay for three nights, which I felt would be enough. Close to the hills, the small Hambukushu village seemed quiet, just a few goats and barefooted children wandered around. Further on we found a new thatched gatehouse and museum building. Organised and well-built structures, perhaps erected in anticipation of UNESCO proclaiming the hills as Botswana’s first World Heritage Site. Later that year, in December 2001, this would spread the fame of the hills around the globe. But for now they were neither staffed nor open, so we chose ourselves a campsite next to Female Hill, under a giant mongongo tree.

The nearest safari camp was four hours’ drive away, so we brought a Land Rover equipped with everything from fuel, water and food to our own roof-top tent. Along the way we’d collected dead wood for a fire, which now cooked our dinner and cast shadows on the rock beside us. Perhaps it was the presence of that vast, looming stone beside us which made the night seem unusually quiet.

We woke with first light, ate breakfast and drove in search of a guide. I’d remembered a village between two of the hills, but that was deserted. Eventually we found a new one ten minutes’ drive away; the Zhu Bushmen had been moved. Despite Botswana’s many enlightened policies on wildlife, its record with its own Bushmen citizens is often called into question.

The Land Rover sunk into the deep sand as we stopped. I was unsure if the shelters around me were occupied, but soon villagers crowded around to sell us craftwork. Traditional ostrich eggshell jewellery is one of their few sources of income, so we bought a couple of finely made necklaces, before trying hard – in a mix of English, Setswana and gestures – to explain that we needed a guide for the hills. Nobody seemed keen, but eventually a girl and her younger brother were nominated for the job. Both had been silent, so I felt that we’d been fobbed off with the children. However, without speaking the language there was no room for discussion, so we accepted with a forced smile and cleared the back seats for them.

Driving back to the hills, we were surprised. The girl shyly introduced herself as Tsetsana and started to converse happily in English; she was 16 and at home during a holiday from school. Her younger brother, Xashee, was ten and spoke much less, though clearly understood much of what we were saying. With one of Africa’s most prosperous economies, Botswana is putting resources into education, and here in this remote area was living proof of it.

Returning to the hill near our campsite, Tsetsana led us up a steep ravine, strewn with boulders. The bare-footed children bounded ahead, while our clambering made slower progress. Often they’d pause, pointing out rock paintings. This was the main reason we were here: the Tsodilo Hills form the canvas for over 4,500 rock paintings, one of the greatest concentrations anywhere in Africa. For the local people during the Middle Stone Age, the hills were alive with art.

We climbed higher into the ravine, our eyes gradually becoming more accustomed to the light. The paintings seemed to line the ascent like an ancient stairway; some consisting of simple small stick figures, others were scenes with cattle and sheep. Some of the most striking were intricate portraits of wild animals, like the huge rhino, about one metre long, which dominated the top of the ravine. It seemed to have been painted only yesterday, standing out from the orange-yellow stone in bright shades of burgundy.

But this wasn’t just art for art’s sake. The local Zhu Bushmen believe that the hills contain the spirits of the dead, and that powerful gods live there in the caves. Many of the images in the hills depict eland, a sacred animal for the Bushmen. They attribute the paintings to the gods, not their ancestors. Van der Post may have famously described Tsodilo as a “Louvre in the desert”, but it’s much more: it’s a sacred place, adorned with spiritual paintings.

Although the distance was short, it took us most of the day to slowly pick our way to the top of the hill, and gradually down the other side. There we found several large friezes, each with too many pictures to distinguish. On one panel, two unusual images stood out: a penguin and a spouting whale. There seemed little doubt what they were, yet these hills are over 1,000km from the nearest ocean, beside Namibia’s Skeleton Coast. Assume that the Bushmen were innocents caught in a Stone Age time warp and this seems impossible. Surely primitive people would never travel so far? Yet believe the evidence that Bushmen were mining ore in these hills around 1,000 years ago, and trading throughout the region, and the existence of the penguin drawing becomes quite plausible. Along with most commentators, I’d accepted without question the romantic image of the Bushmen as simple, hunter/gatherer people, viewing them in clichéd terms as living relics. It’s the view taken almost universally by the modern media.

Yet here beside us, Tsetsana and Xashee were learning English to survive in the world that they found around them. Just as their ancestors had sometimes traded, travelled, farmed and painted – as well as hunted and gathered – in order to survive in this difficult environment.

Returning to the Land Rover we shared lunch before taking Tsetsana and Xashee back to their village, paying their family for their guiding. The following day we explored another hill with them, the taller but less extensive Male Hill. The climb was tougher, but the views from the top well worth it. Beneath us lay the four hills – Male, Female, the Child and the nameless one – and beyond them the vast Kalahari stretched out on all sides.

We knew that we hadn’t seen a fraction of the treasures here, despite our energetic young guides. So on our final morning we packed slowly and left with sadness. Twenty minutes later, pausing at the crest of a dune, we took a last, long look back. There was a dark cloud looming above the hills; a storm was coming. Slowly bumping away across the sandy ruts, I again vowed that next time I’d spend longer at Tsodilo.

When to go: Contrary to expectations of a ‘desert,’ January to March is the rainy season. Then the Kalahari is at its best. However, if you’re seeking game, then visit in the dry season, from May to November. As this progresses, the game in Chobe, Moremi and the Okavango concentrates near the remaining water. May is my favourite month for the clarity of the air, the lushness of the bush and the scarcity of other visitors, even in the national parks.

Health and safety: The north of the country has a higher risk of malaria than in the south where it is very scarce except after rain; but the sun is always strong, so hats, long-sleeved tops and suncream are essential. At the fly-in safari camps you’ll be well looked after. If you’re driving then you need to plan carefully; travelling with another vehicle (and perhaps a satellite phone) is a wise precaution in the more remote areas.