Jasper James

In Paris, nothing could be hotter than raï, an Algerian version of the blues. Lee Smith takes its biggest star, Cheb Mami, for a night on the town

Jasper James

In Paris, nothing could be hotter than raï, an Algerian version of the blues. Lee Smith takes its biggest star, Cheb Mami, for a night on the town

IT'S MIDNIGHT, AND I'M DRIVING AROUND PARIS WITH A FEW Americans, several French Algerians, and Mohamed Khelifati, a 35-year-old musician better known as Cheb Mami. It's his first night back from Oran—a city on Algeria's Mediterranean coast that's considered the capital of that country's popular music, or raï—and he has plans. The music is on loud in his silver sedan; it's a cut from a sound track he's working on, and when Mami starts to sing along with himself, the car is filled with a beautiful, high-pitched longing that silences the rest of us. It's in Arabic, but as Mami says, you don't need to understand the words, since everyone understands the feeling. And now the articulation of that feeling seems to transform the entire city moving past us. The Paris that was there a moment ago—the Louvre, the shops along Rue de Rivoli, the Tuileries—seems remade in the image of the Obélisque du Luxor, a gift from a 19th-century Egyptian viceroy that stands in the center of the Place de la Concorde. Mami taps in time on the steering wheel and turns to us.

"This," he says, "is how to listen to raï."

Mami, one of France's few pop superstars, embodies the country's current vogue for all things North African. Those under 40 have no experience of France's former holdings in the Maghreb (Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco); they embrace Arab culture with passion and more than a little nostalgia. It's a fascination dense with contradiction: North Africans are the main targets of racial discrimination in France, yet there's more of a Maghrebian flavor in French culture than ever before.

Our first stop is 404, a lively Moroccan restaurant in the Third Arrondissement, where we're given a balcony table. The crowd is mixed—half African, North and West; half hip white Parisians from the fashion and media worlds. While everyone recognizes Mami when he walks in with his manager, Michel Lévy, only the North Africans call out his name and greet him warmly. Especially the women. Mami is handsome, more so when he smiles. His smile is so guileless that it emboldens even the most reserved; he's often asked for his phone number. Is this how he spends his nights, giving out decoy phone numbers?

"No, no," he laughs. "I get recognized, but usually very respectfully. I have a normal life. I go out to dinner with friends, or a friend—sometimes here, sometimes at Mansouria. I'll go to a nightclub to dance. I love salsa." As much as raï?

"No, I love raï more than anything," Mami says. "I go to the cabarets all the time, like the Hammam Club. It was one of the first places where I performed in Paris. We'll go there later." (The Oriental cabarets, as they are known, date to the early part of the 20th century, when Algerians, displaced by French settlers, first came to Paris and Marseilles in large numbers.)

While our food is served—a hot Moroccan soup, assorted couscous dishes, a couple of bowls of harissa—Mami, Lévy, Nidam Abdi, a journalist and record producer, and Abdi's cousin Abdelkrim Tchikou sketch a history of raï.

However distinctly Maghrebian in origin, raï, like so much that issues from the joint history of France and Algeria, is a hybrid. Over the past 20 years or so, Western beats from rock and disco have been added to raï's own rhythms. And thanks largely to Mami—who's touring the United States this summer to promote his new album, Dellali—raï is at last making its way to the mecca of pop music, America.

"Madonna is a big fan of Mami's," Lévy says. "So is Brad Pitt."

But it was Sting, says Mami, "who really opened doors for me in America."

Indeed, Mami's last album, Meli Meli, went double gold worldwide, but until his duet with Sting on last year's hit single "Desert Rose" (which they performed during the pregame show at the Super Bowl this year), his American following was very small and almost exclusively Arab. "I was nervous," Mami says, beating his hand on his heart and smiling, "but it was great to play the Super Bowl."

Mami wears his fame lightly, bantering in Arabic with the waitstaff at 404, but when a few English tourists look to see what all the fuss is about he shrinks into the sofa. He's also shy. He'd much rather sing than talk, and occasionally when there's a lull in the conversation he fills it by singing along quietly with whatever's playing over the restaurant's sound system, as though his voice were the one thing he'll always be comfortable with. He began singing professionally at 12, performing at local weddings.

"I accompanied myself on the accordion," Mami explains. "It was all I could afford."

Most raï singers start young, says Abdi, which is why cheb, Arabic for "young man," is a common appellation; the genre's other major talent is Cheb Khaled. Raï means "advice" or "vision," but in Algeria's current political climate (a pitched battle between the military-backed government and various Islamic fundamentalist parties), "will" is a more resonant translation. For the most part the musicians aren't explicitly political, but their lyrics, if not their lifestyles, often run against the Islamic hard-liners. In the last few years two well-known singers, Cheb Hasni and Matoub Lounes, have been killed, and as with many murders in Algeria it's unclear who was responsible. Few raï musicians can live there safely—Mami's recent visit was conducted under heavy security—and those who do stay risk an awful lot for music about love and lost love.

"The songs are about what happens between men and women," Abdi explains. "It's the blues."

"I love Aretha Franklin!" says Mami.

"Al Green!" Abdi counters.

"Stevie Wonder!" Lévy adds.

As we're settling the bill, there's another gap in the conversation: one of Mami's songs is playing. He's listening somewhat distractedly, but the rest of 404 has come to life. "Parisien du Nord" was a huge hit in France—which may not automatically recommend it to American music fans, but with Mami singing in Arabic, overlaid with a French rap about the travails of North African kids in France, it's one of the best pieces of political pop music since early-nineties American hip-hop.

The song ends with a solo riff that turns into an expansive wail. The entire restaurant is quiet for a few seconds before it erupts in wild applause.

"I'm not a politician," Mami says on our way out. "It's like asking a president to sing. But I have to take up subjects like racism, what it's like to be North African in France."

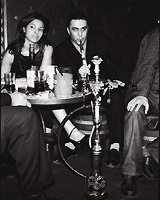

By the time we get to the Hammam Club, the owner is out front to welcome Mami and lead us to a table near the stage, where a 10-piece band is playing through its large repertoire of Maghrebian music. A number of women are dancing together, looking over their shoulders and hoping to catch Mami's eye. Eventually one comes over and asks Abdi's cousin Tchikou for Mami's number; he invents one on the spot.

During a break, the bandleader waves to Mami and announces that they're going to play a set in tribute to Cheb Hasni. Nothing needs explaining; everyone here knows who Hasni was. This is a nightspot for the North African elite—a former soccer star from Morocco, a few lesser-known musicians, successful young businessmen and their dates. They are warm, encouraging us to dance and smoke from the hookah, but we're the only tourists here, and there are no non-African Frenchmen.

I'd noticed the same sense of community on Boulevard Barbès, a largely working-class Maghrebian neighborhood in the 18th Arrondissement, where raï was nurtured in small cafés and music stores long before it exploded internationally. "Raï," Mami says, "is not about politics; it's about daily life."

What's wanted is a city as generous and courageous as raï, a kind of vision. Perhaps the Obélisque du Luxor, given just a year before France took Algeria, should be looked upon not only as a souvenir of the colonial adventure, but as a sort of promise.

ADDRESS BOOK

Restaurants and Clubs

404 Restaurant Familial 69 Rue des Gravilliers, Third Arr.; 33-1/42-74-57-81; dinner for two $52. An indoor garden right out of Arabian Nights. Reserve at least a week in advance — it's that popular.

Music

You can find raï CD's and cassettes in all the large Paris department stores, but walk through the 18th and visit a few of the stores where raï made its Parisian debut, such as Music'In (14 Rue de Chartres; 33-1/42-23-60-71).