Raiders of the Lost

Tafraoute, Morocco

Who among us hasn’t fanned the fading flame of childhood adventure? Occasional thoughts of adventure travel in the realm of lost cities, mysterious people, and hidden treasure are vital to our psyche. Indeed, these momentary journeys may be the one thing that keeps us from plunging our officemates into the paper shredder on Monday mornings.

I’m here to tell you that sometimes, despite ourselves, and in ways we never imagined, these fantasies do come true.

Standing outside Tafraoute, a small town set deep in Morocco’s Anti-Atlas Mountains, I pulled the sweat from my brow and shook my head in disbelief. Patrick, an electrician from Dusseldorf whom I’d just met on the night bus from the coast, held a crude pencil drawing. The colored glyphs of cave drawings and mountains were clear and unambiguous, yet something wasn’t quite right.

Our map, hastily scrawled by a hotel bellboy, indicated a simple circuit of villages and hidden, but “easily located” natural art. Twenty minutes later, off the paved road, we found ourselves lost in the middle of a village that wasn’t on the map.

We lost a few moments fruitlessly questioning adults before two young girls appeared. Rather than running away when we muttered our broken patchwork of “blue rocks”, “colored stones”, and “which way”, the girls led us through back alley kitchens, parlors, and squat archways. Just as I became convinced they’d misunderstood and were taking us home for lunch, we ducked through a low, dark, crawlspace and then staggered out into piercing sunlight. The girls pointed off into the desert and disappeared back down the tunnel.

We stood at the head of a rough dirt track leading into flat rocky desert. The map, such as it was, seemed to lead onwards, and we followed. Dazed by the heat, we pounded across hot dusty rocks for well over an hour. At regular intervals the trail disappeared. With blind reliance on the bellman’s map, we staggered on, through arid abandoned farmland.

Just as dogged persistence began to feel like moronic single-mindedness we came upon three young Moroccan men – often cause for concern in these isolated parts. Unwilling to look stupid in front of our contemporaries, we held back on the dull-witted half-French/Moroccan inquiries. Unable to find a common tongue they left us, stranded.

My childhood fantasy overflows with images of a small cave entrance nestled high on a bluff, a perilous climb to reach said cave, and expressions of awe and gratitude to a generous God as I squeeze through the tight dusty entrance and wipe centuries of sand from the face of sublime ancient artifacts. What my fantasy didn’t contain is exactly what we got.

We rounded a flat bend in the trail to find a desolate farmer’s field giving way to a low, unimpressive valley. Yes, the valley did ring with peals of awe and amazement. Said appellations included,

“WHY in the name of God?”

“That can’t be it.”

And the ever popular, “We sweated our ass off for THAT?”

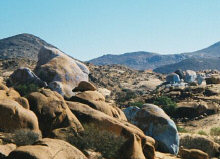

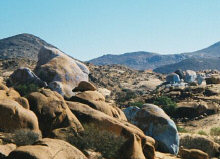

Blue rocks

![]()

![]()

That’s not to say that we weren’t impressed. Oh, we were. When, deep in the heart of a high Moroccan desert you stumble upon a collection of giant rocks painted a flat, milky, house paint blue, one can’t help but be impressed by the shear, naked, absurdity of it all.

In 1984, Belgian artist Jean Veran found his way from Tafraoute to the squat desolate valley that stood before us. It was here that he and his assistants applied (rumor has it) as much as 15 tons of blue paint to rocks indistinguishable from a thousand others on the horizon. Why these? Why here? Why 1984? All of these questions remain unanswered. The artwork itself gives no hint to motive or motif. Scant official records exist of Veran, the blue rocks, or his other works of art. The spectacle of blue rocks in the desert stands alone. Mere existence is the lone voice in their defense.

We explored the valley, climbing high on some of the larger painted rocks.

Patrick and I hoped against all reason that the next cache of desert art would yield more traditional artifacts.

According to the map, our sole tenuous link to civilization, the next leg of the journey should have been a short hop on the trail to a village not far away. An hour later, and no trail in sight, we had no idea where we were.

We stopped frequently to drink from our dwindling water bottles, and to confirm that neither of us was holding anything back. We continued safe in the knowledge that we were both completely lost. Now, past noon, we began to consider the heat less, and the onset of cold darkness a mounting concern.

Reasoning that it must lead to a settlement of some sort, we followed a set of abandoned, crumbling power poles. The way so far had been a series of arid, long-abandoned farm plots, separated by crumbling low stone walls.

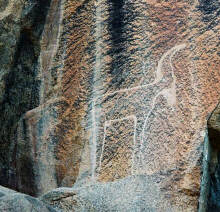

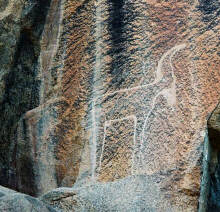

The abandoned farmland began to slope consistently into a canyon of sorts. Believing that the slope must lead to water and the village, we continued our march towards the gazelle, a small chalk sketch rumored to sit on a rock not far from the village that ages ago seemed so close.

Continuing for perhaps another hour we came upon an intact earthen house, housing a father and son. All smiles and warm greetings, they stepped away from their ragged band of half a dozen stringy goats. Tired, and long since disabused of our self-esteem, we asked after the location of the chalk drawing and were rewarded with a wide-eyed stare, a chorus of “la gazelle“, and a vague gesture in the direction we’d been traveling.

Forward ho. The trudge continued.

The Oasis

![]()

![]()

Some long while later, we were back in dusty farm country, a craggy moonscape of abandoned garden plots and overgrazed land. Clearly this had once been a land of abundance, or at the very least the home of dogged optimists. Later, canyons walls began to reappear, and then, suddenly, we turned a corner into heaven, an oasis of palm trees, grass, and the tiniest of streams.

Following the water, we soon found a village. In the mountains of Morocco this consists of a store, a vague patchwork of garden plots, and a few small homes. Was it “the village”? Who knew? Who cared? They had cold drinks.

Alas, none of the locals would freely admit to the whereabouts of “la gazelle“. On the edge of town, one old man grudgingly consented to lead us to it, for a small fee. Exhausted, we conceded. With great ceremony, and money in hand, he led us to a small corral holding the scrawniest of goats.

After several unsuccessful attempts to reckon our map with the land in front of us we came upon an old woman who offered up the broadest of smiles. Finally, and with nary a hint of ceremony or obligation, she led us through palm fronds and dense grass, off trail and through the stream, to a non-descript rock on a bluff about six feet above the village. Here, in a place uncharted by bellboy, entrepreneurial farmer, and well beyond our route-finding skills, sat two small chiseled gazelles.

la Gazelle

![]()

![]()

Perhaps I was just tired, but on the short final walk back into Tafraoute the ever-present assault of pleading rug merchants were muted and far less abrasive than normal. My mind was elsewhere, still lost in the desert.

Later I gazed past the open window of my room at distant mountains and felt immensely thankful for the people who helped me get this far. This group, I realized, included angry rug merchants, and the chiseling old man with one scrawny goat. Without their burdens the trip would have been incomplete.

The things I remembered were not the painted rocks or “la gazelle”, but the smile on an old woman’s face, the young girls’ complete surprise at finding us on their doorstep, and not knowing what was coming at us next.

The real treasure was the chance to get good and lost for a while.